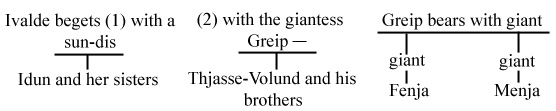

|

When the war between the Asas and the Vans had broken out, Svipdag, as we have learned, espouses the cause of the Vans (see Nos. 33, 38), to whom he naturally belongs as the husband of the Vana-dis Freyja and Frey’s most intimate friend. The happy issue of the war for the Vans gives Svipdag free hands in regard to Halfdan’s hated son Hadding, the son of the woman for whose sake Svipdag’s mother Groa was rejected. Meanwhile Svipdag offers Hadding reconciliation, peace, and a throne among the Teutons (see No. 38). When Hadding refuses to accept gifts of mercy from the slayer of his father, Svipdag persecutes him with irreconcilable hate. This hatred finally produces a turning-point in Svipdag’s fortunes and darkens the career of the brilliant hero. After the Asas and Vans had become reconciled again, one of their first thoughts must have been to put an end to the feud between the Teutonic tribes, since a continuation of the latter was not in harmony with the peace restored among the gods (see No. 41). Nevertheless the war was continued in Midgard (see No. 41), and the cause is Svipdag. He has become a rebel against both Asas and Vans, and herein we must look for the reason why, as we read in the Younger Edda, he disappeared |

|

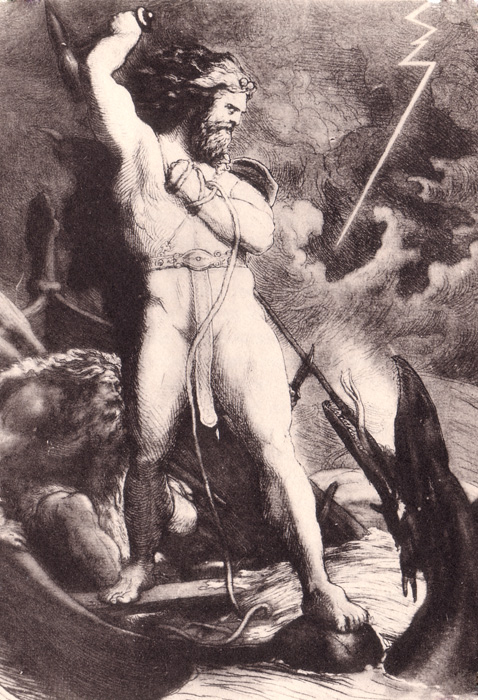

from Asgard (Younger Edda, 114). But he disappears not only from the world of the gods, but finally also from the terrestrial seat of war, and that god or those gods who were to blame for this conceal his unhappy and humiliating fate from Freyja. It is at this time that the faithful and devoted Vana-dis goes forth to seek her lover in all worlds (med ukunnum thjódum). Saxo gives us two accounts of Svipdag’s death — the one clearly converted into history, the other corresponiding faithfully with the mythology. The former reports that Hadding conquered and slew Svipdag in a naval battle (Hist., 42). The latter gives us the following account (Hist., 48): While Hadding lived in exile in a northern wilderness, after his great defeat in conflict with the Swedes, it happened, on a sunny, warm day, that he went to the sea to bathe. While he was washing himself in the cold water he saw an animal of a most peculiar kind (bellua inauditi generis), and came into combat with it. Hadding slew it with quick blows and dragged it on shore. But while he rejoiced over this deed a woman put herself in his way and sang a song, in which she let him know that the deed he had now perpetrated should bring fearful consequences until he succeded in reconciling the divine wrath which this murder had called down upon his head. All the forces of nature, wind and wave, heaven and earth, were to be his enemies unless he could propitiate the angry gods, for the being whose life he had taken was a celestial being concealed in the guise of an animal, one of the super-terrestrial: |

|

It appears, however, from the continuation of the narrative, that Hadding was unwilling to repent what he had done, although he was told that the one he had slain was a supernatural being, and that he long refused to propitiate those gods whose sorrow and wrath he had awakened by the murder. Not until the predictions of the woman were confirmed by terrible visitations does Hadding make up his mind to reconcile the powers in question. And this he does by instituting the sacrificial feast, which is called Frey’s offering, and thenceforth was celebrated in honour of Frey (Fro deo rem divinam furvis hostiis fecit). Hadding’s refusal to repent what he had done, and the defiance he showed the divine powers, whom he had insulted by the murder he had committed, can only be explained by the fact that these powers were the Vana-gods who long gave succour to his enemies (see No. 39), and that the supernatural being itself, which, concealed in the guise of an animal, was slain by him, was some one whose defeat gave him pleasure, and whose death he considered himself bound and entitled to cause. This explanation is fully corroborated by the fact that when he learns that Odin and the Asas, whose favourite he was, no longer hold their protecting hands over him, and that the propitiation advised by the prophetess becomes a necessity to him, he institutes the great annual offering to Frey, Svipdag’s brother-in-law. That this god especially must be propitiated can, again, have no other reason |

|

than the fact that Frey was a nearer kinsman than any of the Asa-gods to the supernatural being, from whose slayer he (Frey) demanded a ransom. And as Saxo has already informed us that Svipdag perished in a naval engagement with Hadding, all points to the conclusion that in the celestial person who was concealed in the guise of an animal and was slain in the water we must discover Svipdag Freyja’s husband. Saxo does not tell us what animal guise it was. It must certainly have been a purely fabulous kind, since Saxo designates it as bellua inauditi generis. An Anglo-Saxon record, which is to be cited below, designates it as uyrm and draca. That Svipdag, sentenced to wear this guise, kept himself in the water near the shore of a sea, follows from the fact that Hadding meets and kills him in the sea where he goes to bathe. Freyja, who sought her lost lover everywhere, also went in search for him to the realms of Ćgir and Rán. There are reasons for assuming that she found him again, and, in spite of his transformation and the repulsive exterior he thereby got, she remained with him and sought to soothe his misery with her faithful love. One of Freyja’s surnames shows that she at one time dwelt in the bosom of the sea. The name is Mardöll. Another proof of this is the fragment preserved to our time of the myth concerning the conflict between Heimdal and Loke in regard to Brisingamen. This neck- and breast-ornament, celebrated in song both among the Teutonic tribes of England and those of Scandinavia, one of the most splendid works of the ancient artists, belonged to Freyja (Thrymskvida, Younger Edda). |

|

She wore it when she was seeking Svipdag and found him beneath the waves of the sea; and the splendour which her Brisingamen diffused from the deep over the surface of the sea is the epic interpretation of the name Mardöll from mar, “sea,” and döll, feminine of dallr (old English deall, “glittering” (compare the names Heimdallr and Delling). Mardöll thus means “the one diffusing a glimmering in the sea.” The fact that Brisingamen, together with its possessor, actually was for a time in Ćgir’s realm is proved by its epithet fagrt hafnýra, “the fair kidney of the sea,” which occurs in a strophe of Ulf Uggeson (Younger Edda, 268). There was also a skerry, Vágasker, Singasteinn, on which Brisingamen lay and glittered, when Loke, clad in the guise of a seal, tried to steal it. But before he accomplished his purpose, there crept upon the skerry another seal, in whose looks — persons in disguise were not able to change their eyes — the evil and cunning descendant of Farbauti must quickly have recognised his old opponent Heimdal. A conflict arose in regard to the possession of the ornament, and the brave son of the nine mothers became the victor and preserved the treasure for Asgard. To the Svipdag synonyms Ódr (Hotharus), Óttar (Otharus), Eirekr (Ericus), and Skirnir, we must finally add one more, which is, perhaps, of Anglo-Saxon origin: Hermodr, Heremod. From the Norse mythic records we learn the following in regard to Hermod: (a) He dwelt in Asgard, but did not belong to the number of the ruling gods. He is called Odin’s sveinn (Younger Edda, 174), |

|

and he was the Asa-father’s favourite, and received from him helmet and cuirass (Hyndluljod, 2). (b) He is called enn hvati (Younger Edda, 174), the rapid. When Frigg asks if anyone desires to earn her favour and gratitude by riding to the realm of death and offering Hel a ransom for Balder, Hermod offers to take upon himself this task. He gets Odin’s horse Sleipnir to ride, proceeds on his way to Hel, comes safely to that citadel in the lower world, where Balder and Nanna abide the regeneration of the earth, spurs Sleipnir over the castle wall, and returns to Asgard with Hel’s answer, and with the ring Draupner, and with presents from Nanna to Frigg and Fulla (Younger Edda, 180). From this it appears that Hermod has a position in Asgard resembling Skirner’s; that he, like Skirner, is employed by the gods as a messenger when important or venturesome errands are to be undertaken; and that he, like Skirir, then gets that steed to ride, which is able to leap over vafurflames and castle-walls. We should also bear in mind that Skirner-Svipdag had made celebrated journeys in the same world to which Hermod is now sent to find Balder. As we know, Svipdag had before his arrival in Asgard travelled all over the lower world, and had there fetched the sword of victory. After his adoption in Asgard, he is sent by the gods to the lower world to get the chain Gleipner. (c) In historical times Hermod dwells in Valhal, and is one of the chief einherjes there. When Hakon the Good was on the way to the hall of the Asa-father, the latter sent Brage and Hermod to meet him: |

|

This is all there is in the Norse sources about Hermod. Further information concerning him is found in the Beowulf poem, which in two passages (str. 1747, &c., and 3419, &c.) compares him with its own unselfish and blameless hero, Beowulf, in order to make it clear that the latter was in moral respects superior to the famous hero of antiquity. Beowulf was related by marriage to the royal dynasty then reigning in his land, and was reared in the king’s halls as an older brother of his sons. The comparisons make these circumstances, common to Beowulf and Hermod, the starting-point, and show that while Beowulf became the most faithful guardian of his young foster-brothers, and in all things maintained their rights, Hermod conducted himself in a wholly different manner. Of Hermod the poem tells us: (a) He was reared at the court of a Danish king (str. 1818, &c., 3422, &c.). (b) He set out on long journeys, and became the most celebrated traveller that man ever heard of (se wćs wreccena wide mśrost ofer wer-theóde — str. 1800-1802). (c) He performed great exploits (str. 1804). (d) He was endowed with powers beyond all other men (str. 3438-39). (e) God gave him a higher position of power than that accorded to mortals (str. 3436, &c.). |

|

(f) But although he was reared at the court of the Danish king, this did not turn out to the advantage of the Skjoldungs, but was a damage to them (str. 3422, &c.), for there grew a bloodthirsty heart in his breast. (g) When the Danish king died (the poem does not say how) he left young sons. (h) Hermod, betrayed by evil passions that got the better of him, was the cause of the ruin of the Skjoldungs, and of a terrible plague among the Danes, whose fallen warriors for his sake covered the battlefields. His table-companions at the Danish court he consigned to death in a fit of anger (str. 3426, &c.). (i) The war continues a very long time (str. 1815, &c., str. 3447). (k) At last there came a change, which was unfavourable to Hermod, whose superiority in martial power decreased (str. 1806). (l) Then he quite unexpectedly disappeared (str. 3432) from the sight of men. (m) This happened against his will. He had suddenly been banished and delivered to the world of giants, where “waves of sorrow” long oppressed him (str. 1809, &c.). (n) He had become changed to a dragon (wyrm, draca). (o) The dragon dwelt near a rocky island in the sea under harne stan (beneath a grey rock). (p) There he slew a hero of the Volsung race (in the Beowulf poem Sigemund — str. 1747, &c.). All these points harmonise completely with Svipdag’s |

|

saga, as we have found it in other sources. Svipdag is the stepson of Halfdan the Skjoldung, and has been reared in his halls, and dwells there until his mother Groa is turned out and returns to Orvandel. He sets out like Hermod on long journeys, and is doubtless the most famous traveller mentioned in the mythology; witness his journey across the Elivagar, and his visit to Jotunheim while seeking Frey and Freyja; his journey across the frosty mountains, and his descent to the lower world, where he traverses Nifelheim, sees the Eylud mill, comes into Mimer’s realm, procures the sword of victory, and sees the glorious castle of the ásmegir; witness his journey over Bifrost to Asgard, and his warlike expedition to the remote East (see also Younger Edda, i. 108, where Skirner is sent to Svartalfaheim to fetch the chain Glitner). He is, like Hermod, endowed with extraordinary strength, partly on account of his own inherited character, partly on account of the songs of incantation sung over him by Groa, on account of the nourishment of wisdom obtained from his stepmother, and finally on account of the possession of the indomitable sword of victory. By being adopted in Asgard as Freyja’s husband, he is, like Hermod, elevated to a position of power greater than that which mortals may expect. But all this does not turn out to be a blessing to the Skjoldungs, but is a misfortune to them. The hatred he had cherished toward the Skjoldung Halfdan is transferred to the son of the latter, Hadding, and he persecutes him and all those who are faithful to Hadding, makes war against him, and is unwilling to end the long war, although the gods demand |

|

it. Then he suddenly disappears, the divine wrath having clothed him with the guise of a strange animal, and relegated him to the world of water-giants, where he is slain by Hadding (who in the Norse heroic saga becomes a Volsung, after Halfdan, under the name Helge Hundingsbane, was made a son of the Volsung Sigmund). Hermod is killed on a rocky island under harne stan. Svipdag is killed in the water, probably in the vicinity of the Vágasker and the Singasteinn, where the Brisingamen ornament of his faithful Mardol is discovered by Loke and Heimdal. Freyja’s love and sorrow may in the mythology have caused the gods to look upon Svipdag’s last sad fate and death as a propitiation of his faults. The tears which the Vana-dis wept over her lover were transformed, according to the mythology, into gold, and this gold, the gold of a woman’s faithfulness, may have been regarded as a sufficient compensation for the sins of her dear one, and doubtless opened to Svipdag the same Asgard-gate which he had seen opened to him during his life. This explains that Hermod is in Asgard in the historical time, and that, according to a revelation to the Swedes in the ninth century, the ancient King Erik was unanimously elevated by the gods as a member of their council. Finally, it should be pointed out that the Svipdag synonym Ódr has the same meaning as môd in Heremôd, and as ferhd in Svidferhd, the epithet with which Hermod is designated in the Beowulf strophe 1820. Ódr means “the one endowed with spirit,” Heremôd “the one endowed with martial spirit,” Svidherhd “the one endowed with mighty spirit.” |

|

Heimdal’s and Loke’s conflict in regard to Brisingamen has undoubtedly been an episode in the mythic account of Svipdag’s last fortunes and Freyja’s abode with him in the sea. There are many reasons for this assuniption. We should bear in mind that Svipdag’s closing career constituted a part of the great epic of the first world war, and that both Heimdal and Loke take part in this war, the former on Hadding’s, the latter on Gudhorm-Jormunrek’s and Svipdag’s side (see Nos. 38, 39, 40). It should further be remembered that, according to Saxo, at the time when he slays the monster, Hadding is wandering about as an exile in the wildernesses, and that it is about this time that Odin gives him a companion and protector in Liserus-Heimdal (see No. 40). The unnamed woman, who after the murder had taken place puts herself in Hadding’s way, informs him whom he has slain, and calls the wrath of the gods and the elements down upon him, must be Freyja herself, since she witnessed the deed and knew who was concealed in the guise of the dragon. So long as the latter lived Brisingamen surely had a faithful watcher, for it is the nature of a dragon to brood over the treasures he finds. After being slain and dragged on shore by Hadding, his “bed,” the gold, lies exposed to view on Vagasker, and the glimmer of Brisingamen reaches Loke’s eyes. While the woman, in despair on account of Svipdag’s death, stands before Hadding and speaks to him, the ornament has no guardian, and Loke finds the occasion convenient for stealing it. But Heimdal, Hadding’s protector, who in the mythology always keeps his eye on the acts of Loke and on his kinsmen |

|

hostile to the gods, is also present, and he too has seen Brisingamen. Loke has assumed the guise of a seal, while the ornament lies on a rock in the sea, Vágasker, and it can cause no suspicion that a seal tries to find a resting-place there. Heimdal assumes the same guise, the seals fight on the rock, and Loke must retire with his errand unperformed. The rock is also called Singasteinn (Younger Edda, i. 264, 268), a name in which I see the Anglo-Saxon Sincastân, “the ornament rock.” An echo of the combat about Brisingamen reappears in the Beowulf poem, where Heimdal (not Hamdir) appears under the name Hâma, and where it is said that “Hâma has brought to the weapon-glittering citadel (Asgard) Brosingamene,” which was “the best ornament under heaven”; whereupon it is said that Hâma fell “into Eormenric’s snares,” with which we should compare Saxo’s account of the snares laid by Loke, Jormenrek’s adviser, for Liserus-Heimdal and Hadding.*

The mythic story about Svipdag and Freyja has been handed down in popular tales and songs, even to our time, of course in an ever varying and corrupted form. Among the popular tales there is one about Mśrthöll, put in writing * As Jordanes confounded the mythological

Gudhorm-Jormunrek with the historical Ermanarek, and connected with the

history of the latter the heroic saga of Ammius-Hamdir, it lay close at

hand to confound Hamdir with Heimdal, who, like Hamdir, is the foe of the

mythical Jormunrek. |

|

by Konrad Maurer, and published in Modern Icelandic Popular Tales. The wondrous fair heroine in this tale bears Freyja’s well-known surname, Mardol, but little changed. And as she, like Freyja, weeps tears that change into gold, it is plain that she is originally identical with the Vana-dis, a fact which Maurer also points out. Like Freyja, she is destined by the norn to be the wife of a princely youth. But when he courted her, difficulties arose which remind us of what Saxo relates about Otharus and Syritha. As Saxo represents her, Syritha is bound as it were by an enchantment, not daring to look up at her lover or to answer his declarations of love. She flies over the mountains more pristino, “in the manner usual in antiquity,” consequently in all probability in the guise of a bird. In the Icelandic popular tale Marthol shudders at the approaching wedding night, since she is then destined to be changed into a sparrow. She is about to renounce the embrace of her lover, so that he may not know anything about the enchantment in which she is fettered. In Saxo the spell resting on Syritha is broken when the candle of the wedding night burns her hand. In the popular tale Marthol is to wear the sparrow guise for ever if it is not burnt on the wedding night or on one of the two following nights. Both in Saxo and in the popular tale another maiden takes Mardol’s place in the bridal bed on the wedding night. But the spell is broken by fire, after which both the lovers actually get each other. |

|

The original identity of the mythological Freyja-Mardol, Saxo’s Syritha, and the Mśrthöll of the Icelandic popular tale is therefore evident. In Danish and Swedish versions of a ballad (in Syv, Nyerup, Arwidsson, Geijer and Afzelius, Grundtvig, Dybeck, Hofberg; compare Bugge’s Edda, p. 352, &c.) a young Sveidal (Svedal, Svendal, Svedendal, Silfverdal) is celebrated, who is none other than Svipdag of the mythology. Svend Grundtvig and Bugge have called attention to the conspicuous similarity between this ballad on the one hand, and Grogalder and Fjölsvinnsmal on the other. From the various versions of the ballad it is necessary to mention here only those features which best preserve the most striking resemblance to the mythic prototype. Sveidal is commanded by his stepmother to find a maiden “whose sad heart had long been longing.” He then goes first to the grave of his deceased mother to get advice from her. The mother speaks to him from the grave and promises him a horse, which can bear him over sea and land, and a sword hardened in the blood of a dragon and resembling fire. The narrow limits of the ballad forbade telling how Sveidal came into possession of the treasures promised by the mother or giving an account of the exploits he performed with the sword. This plays no part in the ballad; it is only indicated that events not recorded took place before Sveidal finds the longing maid. Riding through forests and over seas, he comes to the country where she has her castle. Outside of this he meets a shepherd, with whom he enters into conversation. The shepherd informs him that within is found |

|

a young maiden who has long been longing for a young man by name Sveidal, and that none other than he can enter there, for the timbers of the castle are of iron, its gilt gate of steel, and within the gate a lion and a white bear keep watch. Sveidal approaches the gate; the locks fall away spontaneously; and when he enters the open court the wild beasts crouch at his feet, a linden-tree with golden leaves bends to the ground before him, and the young maiden whom he seeks welcomes him as her husband. One of the versions makes him spur his horse over the castle wall; another speaks of seven young men guarding the wall, who show him the way to the castle, and who in reality are “god’s angels under the heaven, the blue.” The horse who bears his rider over the salt sea is a reminiscence of Sleipnir, which Svipdag rode on more than one occasion; and when it is stated that Sveidal on this horse galloped over the castle wall, this reminds us of Skirner-Svipdag when he leaps over the fence around Gymer’s abode, and of Hermod-Svipdag when he spurs Sleipnir over the wall to Balder’s lower-world castle. The shepherds, who are “god’s angels,” refer to the watchmen mentioned in Fjölsvinnsmal, who are gods; the wild beasts in the open court to the two wolf-dogs who guard Asgard’s gate; the shepherd whom Sveidal meets outside of the wall to Fjölsvin; the linden-tree with the golden leaves to Mimameidr and to the golden grove growing in Asgard. One of the versions makes two years pass while Sveidal seeks the one he is destined to marry. |

|

In Germany, too, we have fragments preserved of the myth about Svipdag and Freyja. These remnants are, we admit, parts of a structure built, so to speak, in the style of the monks, but they nevertheless show in the most positive manner that they are borrowed from the fallen and crumbled arcades of the heathen mythology. We rediscover in them the old medieval poem about “Christ’s unsewed grey coat.” The hero in the poem is Svipdag, here called by his father’s name Orendel, Orentel — that is, Orvandel. The father himself, who is said to be a king in Trier, has received another name, which already in the most ancient heathen times was a synonym of Orvandel, and which I shall consider below. This in connection with the circumstance that the younger Orentel’s (Svipdag’s) patron saint is called “the holy Wieland,” and thus has the name of a person who, in the mythology, as shall be shown below, was Svipdag’s uncle (father’s brother) and helper, and whose sword is Svipdag’s protection and pledge of victory, proves that at least in solitary instances not only the events of the myth but also its names and family relations have been preserved in a most remarkable and faithful manner through centuries in the minds of the German people. In the very nature of things it cannot in the monkish poem be the task of the young Svipdag-Orentel to go in search of the heathen goddess Freyja and rescue her from the power of the giants. In her stead appears a “Frau Breyde,” who is the fairest of all women, and the only one worthy to be the young Orentel’s wife. In the |

|

heathen poem the goddess of fate Urd, in the German medieval poem God Himself, resolves that Orentel is to have the fairest woman as his bride. In the heathen poem Freyja is in the power of giants, and concealed somewhere in Jotunheim at the time when Svipdag is commanded to find her, and it is of the greatest moment for the preservation of the world that the goddess of love and fertility should be freed from the hands of the powers of frost. In the German poem, written under the influence of the efforts of the Christian world to reconquer the Holy Land, Frau Breyde is a princess who is for the time being in Jerusalem, surrounded and watched by giants, heathens, and knights templar, the last of whom, at the time when the poem received its present form, were looked upon as worshippers of the devil, and as persons to be shunned by the faithful. To Svipdag’s task of liberating the goddess of love corresponds, in the monkish poem, Orentel’s task of liberating Frau Breyde from her surrounding of giants, heathens, and knights templar, and restoring to Christendom the holy grave in Jerusalem. Orentel proceeds thither with a fleet. But although the journey accordingly is southward, the mythic saga, which makes Svipdag journey across the frost-cold Elivagar, asserts itself; and as his fleet could not well be hindered by pieces of ice on the coast of the Holy Land, it is made to stick fast in “dense water,” and remain there for three years, until, on the supplication of the Virgin Mary, it is liberated therefrom by a storm. The Virgin Mary’s prayers have assumed the same place in the Christian poems as Groa’s incantations in the |

|

heathen. The fleet, made free from the “dense water,” sails to a land which is governed by one Belian, who is conquered by Orentel in a naval engagement. This Belian is the mythological Beli, one of those “howlers” who surrounded Frey and Freyja during their sojourn in Jotunheim and threatened Svipdag’s life. In the Christian poem Bele was made a king in Great Babylonia, doubtless for the reason that his name suggested the biblical “Bel in Babel.” Saxo also speaks of a naval battle in which Svipdag-Ericus conquers the mythic person, doubtless a storm-giant, who by means of witchcraft prepares the ruin of sailors approaching the land where Frotho and Gunvara are concealed. After various other adventures Orentel arrives in the Holy Land, and the angel Gabriel shows him the way to Frau Breyde, just as “the seven angels of God” in one of the Scandinavian ballads guide Sveidal to the castle where his chosen bride abides. Lady Breyde is found to be surrounded by none but foes of Christianity — knights templar, heathens, and giants — who, like Gunvara’s giant surroundings in Saxo, spend their time in fighting, but still wait upon the fair lady as their princess. The giants and knights templar strive to take Orentel’s life, and, like Svipdag, he must constantly be prepared to defend it. One of the giants slain by Orentel is a “banner-bearer.” One of the giants, who in the mythology tries to take Svipdag’s life, is Grepp, who, according to Saxo, meets him in derision with a banner on the top of whose staff is fixed the head of an ox. Meanwhile Lady Breyde is attentive to Orentel. As Menglad receives Svipdag, so Lady Breyde receives |

|

Orentel with a kiss and a greeting, knowing that he is destined to be her husband. When Orentel has conquered the giants he celebrates a sort of wedding with Lady Breyde, but between them lies a two-edged sword, and they sleep as brother and sister by each other’s side. A wedding of a similar kind was mentioned in the mythology in regard to Svipdag and Menglad before they met in Asgard and were finally united. The chaste chivalry with which Freyja is met in the mythology by her rescuer is emphasised by Saxo both in his account of Ericus-Svipdag and Gunvara and in his story about Otharus and Syritha. He makes Ericus say of Gunvara to Frotho: Intacta illi pudicitia manet (Hist., 126). And of Otharus he declares: Neque puellam stupro violare sustinuit, nec splendido loco natam obscuro concubitus genere macularet (Hist., 331). The first wedding of Orentel and Breyde is therefore as if it had not been, and the German narrative makes Orentel, after completing other warlike adventures, sue for the hand of Breyde for the second time. In the mythology the second and real wedding between Svipdag and Freyja must certainly have taken place, inasmuch as he becamne reunited with her in Asgard. The sword which plays so conspicuous a part in Svipdag’s fortunes has not been forgotten in the German medieval tale. It is mentioned as being concealed deep down in the earth, and as a sword that is always attended by victory. On one occasion Lady Breyde appears, weapon in hand, and fights by the side of Orentel, under circumstances |

|

which remind us of the above-cited story from Saxo (see No. 102), when Ericus-Svipdag, Gunvara-Freyja, and Rollerus-Ull are in the abode of a treacherous giant, who tries to persuade Svipdag to deliver Gunvara to him, and when Bracus-Thor breaks into the giant abode, and either slays the inmates or puts them to flight. Gunvara then fights by the side of Ericus-Svipdag, muliebri corpore virilem animum śquans (Hist., 222). In the German Orentel saga appears a “fisherman,” who is called master Yse. Orentel has at one time been wrecked, and comes floating on a plank to his island, where Yse picks him up. Yse is not a common fisherman. He has a castle with seven towers, and eight hundred fishermen serve under him. There is good reason for assuming that this mighty chieftain of fishermen originally was the Asa-god Thor, who in the northern ocean once had the Midgard-serpent on his hook, and that the episode of the picking up of the wrecked Orentel by Yse has its root in a tradition concerning the mythical adventure, when the real Orvandel, Svipdag’s father, feeble and cold, was met by Thor and carried by him across the Elivagar. In the mythology, as shall be shown hereafter, Orvandel the brave was Thor’s “sworn” man, and fought with him against giants before the hostility sprang up between Ivalde’s sons and the Asa-gods. In the Orentel saga Yse also regands Orentel as his “thrall.” The latter emancipates himself from his thraldom with gold. Perhaps this ransom is a reference to the gold which Freyja’s tears gave as a ransom for Svipdag. Orentel’s father is called Eigel, king in Trier. In |

|

Vilkinasaga we find the archer Egil, Volund’s brother, mentioned by the name-variation Eigill. The German Orentel’s patron saint is Wieland, that is, Volund. Thus in the Orentel saga as in the Volundarkvida and in Vilkinasaga we find both these names Egil and Volund combined, and we have all the more reason for regarding King Eigel in Trier as identical with the mythological Egil, since the latter, like Orvandel, is a famous archer. Below, I shall demonstrate that the archer Orvandel and the archer Egil actually were identical in the mythology. But first it may be in order to point out the following circumstances. Tacitus tells us in his Germania (3): “Some people think, however, that Ulysses, too, on his long adventurous journeys was carried into this ocean (the Germanic), and visited the countries of Germany, and that he founded and gave name to Asciburgium, which is situated on the Rhine, and is still an inhabited city; nay, an altar consecrated to Ulysses, with the name of his father Laertes added, is said to have been found there.” To determine the precise location of this Asciburgium is not possible. Ptolemy (ii. 11, 28), and after him Marcianus Heracleota (Peripl., 2, 36), inform us that an Askiburgon was situated on the Rhine, south of and above the delta of the river. Tabula Peutingeriana locates Asceburgia between Gelduba (Gelb) and Vetera (Xanten). But from the history of Tacitus it appears (iv. 33) that Asciburgium was situated between Neuss and Mainz (Mayence). Read the passage: Aliis a Novśsio, aliis a Mogontiaco universas copias advenisse credentibus. |

|

The passage refers to the Roman troops sent to Asciburgium and there attacked — those troops which expect to be relieved from the nearest Roman quarters in the north or south. Its location should accordingly be looked for either on or near that part of the Rhine, which on the east bordered the old archbishopric Trier. Thus the German Orentel saga locates King Eigel’s realm and Orentel’s native country in the same regions, where, according to Tacitus’ reporter, Ulysses was said to have settled for some time and to have founded a citadel. As is well known, the Romans believed they found traces of the wandering Ulysses in well-nigh all lands, and it was only necessary to hear a strange people mention a far-travelled mythic hero, and he was at once identified either as Ulysses or Hercules. The Teutonic mythology had a hero ŕ la Ulysses in the younger Orentel, Oder-Svipdag-Heremod, whom the Beowulf poem calls “incomparably the most celebrated traveller among mankind” (wreccena wide mśrost ofer wer-theóde). Mannhardt has already pointed out an episode (Orentel’s shipwreck and arrival in Yse’s land) which calls to mind the shipwreck of Odysseus and his arrival in the land of the Pheaces. Within the limits which the Svipdag-myth, according to my own investigations, proves itself to have had, other and more conspicuous features common to both, but certainly not borrowed from either, can be pointed out, for instance Svipdag’s and Odysseus’ descent to the lower world, and the combat in the guise of seals between Heimdal and Loke, which reminds us of the conflict of Menelaos clad in seal-skin with the seal-watcher Proteus |

|

(Odyss., iv. 404, &c.). Just as there are words in the Aryan languages that in their very form point to a common origin, but not to a borrowing, so there are also myths in the Aryan religions which in their very form reveal their growth from an ancient common Aryan root, but produce no suspicion of their being borrowed. Among these are to be classed those features of the Odysseus and Svipdag myths which resemble each other. It has already been demonstrated above, that Germania’s Mannus is identical with Halfdan of the Norse sources, and that Yngve-Svipdag has his counterpart in Ingćvo (see No. 24). That informer of Tacitus who was able to interpret Teutonic songs about Mannus and his sons, the three original race heroes of the Teutons, must also in those very songs have heard accounts of Orvandel’s and Svipdag’s exploits and adventures, since Orvandel and Svipdag play a most decisive part in the fortunes of Mannus-Halfdan. If the myth about Svipdag was composed in a later time, then Mannus-Halfdan’s saga must have undergone a change equal to a complete transformation after the day of Tacitus, and for such an assumption there is not the slightest reason. Orvandel is not a mythic character of later make. As already pointed out, and as shall be demonstrated below, he has ancient Aryan ancestry. The centuries between Tacitus and Paulus Diaconus are unfortunately almost wholly lacking in evidence concerning the condition of the Teutonic myths and sagas; but where, as in Jordanes, proofs still gleam forth from the prevailing darkness, we find mention of Arpantala, Amala, Fridigernus, Vidigoia (Jord., v.). |

|

Jordanes says that in the most ancient times they were celebrated in song and described as heroes who scarcely had their equals (quales vix heroas fuisse miranda jactat antiquitas). Previous investigators have already recognised in Arpantala Orvandel, in Amala Hamal, in Vidigoia Wittiche, Wieland’s son (Vidga Volundson), who in the mythology are cousins of Svipdag (see No. 108). Fridigernus, Fridgjarn, means “he who strives to get the beautiful one,” an epithet to which Svipdag has the first claim among ancient Teutonic heroes, as Freyja herself has the first claim to the name Frid (beautiful). In Fjölsvinnsmal it belongs to a dis, who sits at Freyja’s feet, and belongs to her royal household. This is in analogy with the fact that the name Hlin belongs at the same time to Frigg herself (Völuspa), and to a goddess belonging to her royal household (Younger Edda, i. 196). What Tacitus tells about the stone found at Asciburgium, with the names of Ulysses and Laertes inscribed thereon, can of course be nothing but a conjecture, based on the idea that the famous Teutonic traveller was identical with Odysseus. Doubtless this idea has been strengthened by the similarity between the names Ódr, Goth. Vods, and Odysseus, and by the fact that the name Laertes (acc. Laerten) has sounds in common with the name of Svipdag’s father. If, as Tacitus seems to indicate, Asciburgium was named after its founder, we would find in Asc- an epithet of Orvandel’s son, common in the first century after Christ and later. In that case it lies nearest at hand to think of aiska (Fick, iii. 5), the English “ask,” the Anglo-Saxon ascian, the Swedish |

|

äska, “to seek,” “search for,” “to try to secure,” which easily adapted itself to Svipdag, who goes on long and perilous journeys to look for Freyja and the sword of victory. I call attention to these possibilities because they appear to suggest an ancient connection, but not for the purpose of building hypotheses thereon. Under all circumstances it is of interest to note that the Christian medieval Orentel saga locates the Teutonic migration hero’s home to the same part of Germany where Tacitus in his time assumed that he had founded a citadel. The tradition, as heard by Tacitus, did not however make the regions about the Rhine the native land of the celebrated traveller. He came thither, it is said in Germania, from the North after having navigated in the Northern Ocean. And this corresponds with the mythology, which makes Svipdag an Ingućon, and Svion, a member of the race of the Skilfing-Ynglings, makes him in the beginning fight on the side of the powers of frost against Halfdan, and afterwards lead not only the north Teutonic (Ingućonian) but also the west Teutonic tribes (the Hermiones) against the east Teutonic war forces of Hadding (see Nos. 38-40). Memories of the Svipdag-myth have also been preserved in the story about Hamlet, Saxo’s Amlethus (Snćbjorn’s Amlodi), son of Horvendillus (Orvandel). In the medieval story Hamlet’s father, like Svipdag’s father in the mythology, was slain by the same man, who marries the wife of the slain man, and, like Svipdag in the myth, Hamlet of the medieval saga becomes the avenger of his father Horvendillus and the slayer of his stepfather. On |

|

more than one occasion the idea occurs in the Norse sagas that a lad whose stepfather had slain his father broods over his duty of avenging the latter, and then plays insane or half idiot to avoid the suspicion that he may become dangerous to the murderer. Svipdag, Orvandel’s son, is reared in his stepfather’s house amid all the circumstances that might justify or explain such a hypocrisy. Therefore he has as a lad received the epithet Amlodi, the meaning of which is “insane,” and the myth having at the same time described him as highly-gifted, clever, and sharp-witted, we have in the words which the mythology has attributed to his lips the key to the ambiguous words which make the cleverness, which is veiled under a stupid exterior, gleam forth. These features of the mythic account of Svipdag have been transferred to the middle-age saga anent Hamlet — a saga which already in Saxo’s time had been developed into an independent narrative. I shall return to this theme in a treatise on the heroic sagas. Other reminiscences of the Svipdag-myth reappear in Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian ballads. The Danish ballads, which, with surprising fidelity, have preserved certain fundamental traits and details of the Svipdag-myth even down to our days, I have already discussed. The Norwegian ballad about “Hermod the Young” (Landstad Norske Folkeviser, p. 28), and its Swedish version, “Bergtrollet,” which corresponds still more faithfully with the myth (Arvidson, i. 123), have this peculiar interest in reference to mythological synonymies and the connection of the mythic fragments preserved, that Svipdag appears in the former as in the Beowulf poem and |

|

in the Younger Edda under the name Hermod, and that both versions have for their theme a story, which Saxo tells about his Otharus when he describes the flight of the latter through Jotunheim with the rediscovered Syritha. It has already been stated above (No. 100) that after Otharus had found Syritha and slain a giant in whose power she was, he was separated from her on their way home, but found her once more and liberated her from a captivity into which she had fallen in the abode of a giantess. This is the episode which forms the theme of the ballad about “Hermod the Young,” and of the Swedish version of it. Brought together, the two ballads give us the following contents: The young Hermod secured as his wife a beautiful maiden whom he liberated from the hands of a giantess. She had fallen into the hands of giants through a witch, “gigare,” originally gýgr, a troll-woman, Aurboda, who in a great crowd of people had stolen her out of a church (the divine citadel Asgard is changed into a “house of God”). Hermod hastens on skees “through woods and caverns and recesses,” comes to “the wild sea-strand” (Elivagar) and to the “mountain the blue,” where the giantess resides who conceals the young maiden in her abode. It is Christmas Eve. Hermod asks for lodgings for the night in the mountain dwelling of the giantess and gets it. Resorting to cunning, he persuades the giantess the following morning to visit her neighbours, liberates the fair maiden during her absence, and flies on his skees with her “over the high mountains and down the low ones.” When the old giantess on her return home |

|

finds that they have gone she hastens (according to the Norwegian version accompanied by eighteen giants) after those who have taken flight through dark forests with a speed which makes every tree bend itself to the ground. When Hermod with his young maiden had come to the salt fjord (Elivagar) the giantess is quite near them, but in the decisive moment she is changed to a stone, according to the Norse version, by the influence of the sun, which just at that time rose; according to the Swedish version, by the influence of a cross which stood near the fjord and its “long bridge.” The Swedish version states, in addition to this, that Hermod had a brother; in the mythology, Ull the skilful skee-runner. In both the versions, Hermod is himself an excellent skee-man. The refrains in both read: “He could so well on the skees run.” Below, I shall prove that Orvandel, Svipdag’s and Ull’s father, is identical with Egil, the foremost skee-runner in the mythology, and that Svipdag is a cousin of Skade, “the dis of the skees.” Svipdag-Hermod belongs to the celebrated skee-race of the mythology, and in this respect, too, these ballads have preserved a genuine trait of the mythology. In their way, these ballads, therefore, give evidence of Svipdag’s identity with Hermod, and of the latter’s identity with Saxo’s Otherus. Finally, a few words about the Svipdag synonyms. Of these, Ódr and Hermodr (and in the Beowulf poem Svidferhd) form a group, which, as has already been pointed out above, refer to the qualities of his mind. Svipdag (“the glimmering day”) and Skirner (“the shining one”) |

|

form another group, which refers to his birth as the son of the star-hero Orvandel, who is “the brightest of stars,” and “a true beam from the sun” (see above). Again, anent the synonym Eirekr, we should bear in mind that Svipdag’s half-brother Gudhorm had the epithet Jormunrekr, and the half-brother of the latter, Hadding, the epithet thódrekr. They are the three half-brothers who, after the patriarch Mannus-Halfdan, assume the government of the Teutons; and as each one of them has large domains, and rules over many Teutonic tribes, they are, in contradistinction to the princes of the separate tribes, great kings or emperors. It is the dignity of a great king which is indicated, each in its own way, by all these parallel names — Eirekr, Jormunrekr, and thjódrekr. Svipdag’s father, Orvandel, must have been a mortal enemy of Halfdan, who abducted his wife Groa. But hitherto it is his son Svipdag whom we have seen carry out the feud of revenge against Halfdan. Still, it must seem incredible that the brave archer himself should remain inactive and leave it to his young untried son to fight against Thor’s favourite, the mighty son of Borgar. The epic connection demands that Orvandel also should take part in this war and it is necessary to investigate |

|

whether our mythic records have preserved traces of the satisfaction of this demand in regard to the mythological epic. As his name indicates, Orvandel was a celebrated archer. That Ör- in Orvandel, in heathen times, was conceived to be the word ör, “arrow” — though this meaning does not therefore need to be the most original one — is made perfectly certain by Saxo, according to whom Örvandill’s father was named Geirvandill (Gervandillus, Hist., 135). Thus the father is the one “busy with the spear,” the son “the one busy with the arrow.” Taking this as the starting point, we must at the very threshold of our investigation present the question: Is there among Halfdan’s enemies mentioned by Saxo anyone who bears the name of a well-known archer? This is actually the fact. Halfdan Berggram has to contend with two mythic persons, Toko and Anundus, who with united forces appear against him (Hist., 325). Toko, Toki, is the well-known name of an archer. In another passage in Saxo (Hist., 265, &c.) one Anundus, with the help of Avo (or Ano) sagittarius, fights against one Halfdan. Thus we have the parallels: The archer Orvandel is an enemy of Halfdan. The man called archer Toko and Anundus are enemies of Halfdan. The archer Avo and Anundus are enemies of Halfdan. What at once strikes us is the fact that both the one called Toko (an archer’s name) and the archer Avo have as comrade one Anundus in the war against Halfdan. Whence did Saxo get this Anundus? We are now in the |

|

domain of mythology related as history, and the name Anund must have been borrowed thence. Can any other source throw light on any mythic person by this name? There was actually an Anund who held a conspicuous place in mythology, and he is none other than Volund. Volundarkvida informs us that Volund was also called Anund. When the three swan-maids came to the Wolfdales, where the three brothers, Volund, Egil, and Slagfin, had their abode, one of them presses Egil “in her white embrace,” the other is Slagfin’s beloved, and the third “lays her arms around Anund’s white neck.”

Volund is the only person by name Anund found in our mythic records. If we now eliminate — of course only for the present and with the expectation of confirmatory evidence — the name Anund and substitute Volund, we get the following parallels: Volund and Toko (the name of an archer) are enemies of Halfdan. Volund and the archer named Avo are enemies of Halfdan. The archer Orvandel is an enemy of Halfdan. From this it would appear that Volund was very intimately associated with one of the archers of the mythology, and that both had some reason for being enemies of Halfdan. Can this be corroborated by any other source? |

|

Volund’s brothers are called Egill and Slagfidr (Slagfinr) in Volundarkvida. The Icelandic-Norwegian poems from heathen times contain paraphrases which prove that the mythological Egil was famous as an archer and skee-runner. The bow is “Egil’s weapon,” the arrows are “Egil’s weapon-hail” (Younger Edda, 422), and “the swift herring of Egil’s hands” (Har. Gr., p. 18). A ship is called Egil’s skees, originally because he could use his skees also on the water. In Volundarkvida he makes hunting expeditions with his brothers on skees. Vilkinasaga also (29, 30) knows Egil as Volund’s brother, and speaks of him as a wonderfully skilful archer. The same Volund, who in Saxo under the name Anund has Toko (the name of an archer) or the archer Avo by his side in the conflict with Halfdan, also has the archer Egil as a brother in other sources. Of an archer Toko, who is mentioned in Hist., 487-490, Saxo tells the same exploit as Vilkinasaga attributes to Volund’s brother Egil. In Saxo it is Toko who performs the celebrated masterpiece which was afterwards attributed to William Tell. In Vilkinasaga it is Egil. The one like the other, amid similar secondary circumstances, shoots an apple from his son’s head. Egil’s skill as a skee-runner and the serviceableness of his skees on the water have not been forgotten in Saxo’s account of Toko. He runs on skees down the mountain, sloping precipitously down to the sea, Kullen in Scania, and is said to have saved himself on board a ship. Saxo’s Toko was therefore without doubt identical with Volund’s brother Egil, and Saxo’s Anund is the same Volund of whom |

|

the Volundarkvida testifies that he also had this name in the mythology. Thus we have demonstrated the fact that Volund and Egil appeared in the saga of the Teutonic patriarch Halfdan as the enemies of the latter, and that the famous archer Egil occupied the position in which we would expect to find the celebrated archer Orvandel, Svipdag’s father. Orvandel is therefore either identical with Egil, and then it is easy to understand why the latter is an enemy of Halfdan, who we know had robbed his wife Groa; or he is not identical with Egil, and then we know no motive for the appearance of the latter on the same side as Svipdag, and we, moreover, are confronted by the improbability that Orvandel does nothing to avenge the insult done to him. Orvandel’s identity with Egil is completely confirmed by the following circumstances. Orvandel has the Elivagar and the coasts of Jotunheim as the scene of his exploits during the time in which he is the friend of the gods and the opponent of the giants. To this time we must refer Horvendillus’ victories over Collerus (Kollr) and his sister Sela (cp. the name of a monster Selkolla — Bisk S., i. 605) mentioned by Saxo (Hist., 135-138). His surname inn frśkni, the brave, alone is proof that the myth refers to important exploits carried out by him, and that these were performed against the powers of frost in particular — that is to say, in the service of the gods and for the good of Midgard — is plain from the narrative in the Younger Edda (276, 277). This shows, as is also demanded by the epic connection, |

|

that the Asa-god Thor and the archer Orvandel were at least for a time confidential friends, and that they had met each other on their expeditions for similar purposes in Jotunheim. When Thor, wounded in his forehead, returns from his combat with the giant Hrungnir to his home, thrúdvángr (thrúdvángar, thrudheimr), Orvandel’s wife Groa was there and tried to help him with healing sorcery, wherein she would also have succeeded if Thor could have made himself hold his tongue for a while concerning a report he brought with him about her husband, and which he expected would please her. And Groa did become so glad that she forgot to continue the magic song and was unable to complete the healing. The report was, as we know, that, on the expedition to Jotunheim from which he had now come home, Thor bad met Orvandel, carried him in his basket across the Elivagar, and thrown a toe which the intrepid adventurer had frozen up to heaven and made a star thereof. Thor added that before long Orvandel would come “home”; that is to say, doubtless, “home to Thor,” to fetch his wife Groa. It follows that, when he had carried Orvandel across the Elivagar, Thor had parted with him somewhere on the way, in all probability in Orvandel’s own home, and that while Orvandel wandered about in Jotunheim, Groa, the dis of growth, had a safe place of refuge in the Asa-god’s own citadel. A close relation between Thor and Orvandel also appears from the fact that Thor afterwards marries Orvandel’s second wife Sif, and adopts his son Ull, Svipdag’s half-brother (see No. 102), in Asgard. Consequently Orvandel’s abode was situated south of |

|

the Elivagar (Thor carried him nordan or Jötunheimum), in the direction Thor had to travel when going to and from the land of the giants, and presumably quite near or on the strand of that mythic water-course over which Thor on this occasion carried him. When Thor goes from Asgard to visit the giants he rides the most of the way in his chariot drawn by the two goats Tanngnjóstr and Tanngrisnir. In the poem Haustlaung there is a particularly vivid description of his journey in his thunder chariot through space when he proceeded to the meeting agreed upon with the giant Hrungner, on the return from which he met and helped Orvandel across Elivagar (Younger Edda, 276). But across this water and through Jotunheim itself Thor never travels in his car. He wades across the Elivagar, he travels on foot in the wildernesses of the giants, and encounters his foe face to face, breast to breast, instead of striking him from above with lightning. In this all accounts of Thor’s journeys to Jotunheim agree. Hence south of the Elivagar and somewhere near them there must have been a place where Thor left his chariot and his goats in safety before he proceeded farther on his journey. And as we already know that the archer Orvandel, Thor’s friend, and like him hostile to the giants, dwelt on the road travelled by the Asa-god, and south of the Elivagar, it lies nearest at hand to assume that Orvandel’s castle was the stopping-place on his journey, and the place where he left his goats and car. Now in Hymerskvida (7, 37, 38) we actually read that Thor, on his way to Jotunheim, had a stopping-place, |

|

where his precious car and goats were housed and taken care of by the host, who accordingly had a very important task, and must have been a friend of Thor and the Asa-gods in the mythology. The host bears the archer name Egil. From Asgard to Egil’s abode, says Hymerskvida, it is about one day’s journey for Thor when he rides behind his goats on his way to Jotunheim. After this day’s journey he leaves the draught-animals, decorated with horns, with Egil, who takes care of them, and the god continues his journey on foot. Thor and Tyr being about to visit the giant Hymer —

(“Nearly all the day they proceeded their way from Asgard until they came to Egil’s. He gave the horn-strong goats care. They (Thor and Tyr) continued to the great hall which Hymer owned.”) From Egil’s abode both the gods accordingly go on foot. From what is afterwards stated about adventures on their way home, it appears that there is a long distance between Egil’s house and Hymer’s (cp. 35 — foro lengi, adr., &c.). It is necessary to journey across the Elivagar first — byr fyr austan Elivága hundviss Hymer (str. 5). In the Elivagar Hymer has his fishing-grounds, |

|

and there he is wont to catch whales on hooks (cp. str. 17 — a vâg roa); but still he does not venture far out upon the water (see str. 20), presumably because he has enemies on the southern strand where Egil dwells. Between the Elivagar and Hymer’s abode there is a considerable distance through woody mountain recesses (holtrid — str. 27) and past rocks in whose caverns dwell monsters belonging to Hymer’s giant-clan (str. 35). Thor resorts to cunning in order to secure a safe retreat. After he has been out fishing with the giant, instead of making his boat fast in its proper place on the strand, as Hymer requests him to do, he carries the boat with its belongings all the difficult way up to Hymer’s hall. He is also attacked on his way home by Hymer and all his giant-clan, and, in order to be able to wield Mjolner freely, he must put down the precious kettle which he has captured from the frost-giant and was carrying on his broad shoulders (str. 35, 36). But the undisturbed retreat across the Elivagar he has secured by the above-mentioned cunning. Egil is called hraunbúi (str. 38), an epithet the ambiguous meaning of which should not be unobserved. It is usually translated with rock-dweller, but it here means “he who lives near or at Hraunn” (Hrönn). Hraunn is one of the names of the Elivagar (see Nos. 59, 93; cp. Younger Edda, 258, with Grimnersmal, 38). After their return to Egil’s, Thor and Tyr again seat themselves in the thunder-chariot and proceed to Asgard with the captured kettle. But they had not driven far before the strength of one of the horn-decorated draught |

|

animals failed, and it was found that the goat was lame (str. 37). A misfortune had happened to it while in Egil’s keeping, and this had been caused by the cunning Loke (str. 37). The poem does not state the kind of misfortune — the Younger Edda gives us information on this point — but if it was Loke’s purpose to make enmity between Thor and his friend Egil he did not succeed this time. Thor, to be sure, demanded a ransom for what had happened, and the ransom was, as Hymerskvida informs us, two children who were reared in Egil’s house. But Thor became their excellent foster-father and protector, and the punishment was therefore of such a kind that it was calculated to strengthen the bond of friendship instead of breaking it. Gylfaginning also (Younger Edda, i. 142, &c.) has preserved traditions showing that when Thor is to make a journey from Asgard to Jotunheim it requires more than one day, and that he therefore puts up in an inn at the end of the first day’s travel, where he eats his supper and stops over night. There he leaves his goats and travels the next day eastward (north), “across the deep sea” (hafit that hit djúpa), on whose other side his giant foes have their abode. The sea in question is the Elivagar, and the tradition correctly states that the inn is situated on its southern (western) side. But Gylfaginning has forgotten the name of the host in this inn. Instead of giving his name it simply calls him a buandi (peasant); but it knows and states on the other hand the names of the two children there reared, Thjalfe and Roskva; and it relates how it happened that |

|

one of Thor’s goats became lame, but without giving Loke the blame for the misfortune. According to Gylfaginning the event occurred when Thor was on his way to Utgard-Loke. In Gylfaginning, too, Thor takes the two children as a ransom, and makes Thjalfe (thjálfi) a hero, who takes an honourable part in the exploits of the god. As shall be shown below, this inn on the road from Asgard to Jotunheim is presupposed as well known in Eilif Gudrunson’s Thorsdrapa, which describes the adventures Thor met with on his journey to the giant Geirrod. Thorsdrapa gives facts of great mythological importance in regard to the inhabitants of the place. They are the “sworn” helpers of the Asa-gods, and when it is necessary Thor can thence secure brave warriors, who accompany him across Elivagar into Jotunheim. Among them an archer plays the chief part in connection with Thjalfe (see No. 114). On the north side of Elivagar dwell accordingly giants hostile to gods and men; on the south side, on the other hand, beings friendly to the gods and bound in their friendship by oaths. The circumstance that they are bound by oaths to the gods (see Thorsdrapa) implies that a treaty has been made with them and that they owe obedience. Manifestly the uttermost picket guard to the north against the frost-giants is entrusted to them. This also gives us an explanation of the position of the star-hero Orvandel, the great archer, in the mythological epic. We can understand why he is engaged to the dis of growth Groa, as it is his duty to defend Midgard against the destructions of frost; and why he fights on |

|

the Elivagar and in Jotunheim against the same enemies as Thor; and why the mythology has made him and the lord of thunder friends who visit each other. With the tenderness of a father, and with the devotion of a fellow-warrior, the mighty son of Odin bears on his shoulders the weary and cold star-hero over the foggy Elivagar, filled with magic terrors, to place him safe by his own hearth south of this sea after he has honoured him with a token which shall for ever shine on the heavens as a monument of Orvandel’s exploits and Thor’s friendship for him. In the meantime Groa, Orvandel’s wife, stays in Thor’s halls. But we discover the same bond of hospitality between Thor and Egil. According to Hymerskvida it is in Egil’s house, according to Gylfaginning in the house in which Thjalfe is fostered, where the accident to one of Thor’s goats happens. In one of the sources the youth whom Thor takes as a ransom is called simply Egil’s child; in the other he is called Thjalfe. Two different mythic sources show that Thjalfe was a waif, adopted in Egil’s house, and consequently not a real brother, but a foster-brother of Svipdag and Ull. One source is Fornaldersaga (iii. 241), where it is stated that Groa in a flśdarmál found a little boy and reared him together with her own son. Flśdarmál is a place which a part of the time is flooded with water and a part of the time lies dry. The other source is the Longobard saga, in which the mythological Egil reappears as Agelmund, the first king of the Longobardians who emigrated from Scandinavia (Origo Longob., Paulus Diac., 14, 15; cp. No. 112). Agelmund, |

|

it is said, had a foster-son, Lamicho (Origo Longob.), or Lamissio (Paulus Diac.), whom he found in a dam and took home out of pity. Thus in the one place it is a woman who bears the name of the archer Orvandel’s wife, in the other it is the archer Egil himself, who adopts as foster-son a child found in a dam or in a place filled with water. Paulus Diaconus says that the lad received the name Lamissio to commemorate this circumstance, “since he was fished up out of a dam or dyke,” which in their (the Longobardian) language is called lama (cp. lehm, mud). The name Thjalfe (thjálfi) thus suggests a similar idea. As Vigfusson has already pointed out, it is connected with the English delve, a dyke; with the Anglo-Saxon delfan; the Dutch delven, to work the ground with a spade, to dig. The circumstances under which the lad was found presaged his future. In the mythology he fells the clay-giant Mökkr-kalfi (Younger Edda, i. 272-274). In the migration saga he is the discoverer of land and circumnavigates islands (Korm., 19, 3; Younger Edda, i. 496), and there he conquers giants (Harbards-ljod, 39) in order to make the lands inhabitable for immigrants. In the appendix to the Gotland law he appears as Thjelvar, who lands in Gotland, liberates the island from trolls by carrying fire, colonises it and becomes the progenitor of a host of emigrants, who settle in southern countries. In Paulus Diaconus he grows up to be a powerful hero; in the mythology he develops into the Asa-god Thor’s brave helper, who participates in his and the great archer’s adventures on the Elivagar and in Jotunheim. Paulus (ch. 15) says that |

|

when Agelmund once came with his Longobardians to a river, “amazons” wanted to hinder him from crossing it. Then Lamissio fought, swimming in the river, with the bravest one of the amazons, and killed her. In the mythology Egil himself fights with the giantess Sela, mentioned in Saxo as an amazon: piraticis exercita rebus ac bellici perita muneris (Hist., 138), while Thjalfe combats with giantesses on Hlessey (Harbardslj., 39), and at the side of Thor and the archer he fights his way through the river waves, in which giantesses try to drown him (Thorsdrapa). It is evident that Paulus Diaconus’ accounts of Agelmund and Lamissio are nothing but echoes related as history of the myths concerning Egil and Thjalfe, of which the Norse records fortunately have preserved valuable fragments. Thus Thjalfe is the archer Egil’s and Groa’s foster-son, as is apparent from a bringing together of the sources cited. From other sources we have found that Groa is the archer Orvandel’s wife. Orvandel dwells near the Elivagar and Thor is his friend, and visits him on his way to and from Jotunheim. These are the evidences of Orvandel’s and Egil’s identity which lie nearest at hand. It has already been pointed out that Svipdag’s father Orvandel appears in Saxo by the name Ebbo (see Nos. 23, 100). It is Otharus-Svipdag’s father whom he calls Ebbo (Hist., 329-333). Halfdan slays Orvandel-Ebbo, while the latter celebrates his wedding with a princess Sygrutha (see No. 23). In the mythology Egil had the same fate: an enemy and rival kills him for the sake of a woman. “Franks Casket,” an old work of sculpture |

|

now preserved in England, and reproduced in George Stephens’ great work on the runes,* represents Egil defending his house against a host of assailants who storm it. Within the house a woman is seen, and she is the cause of the conflict. Like Saxo’s Halfdan, one of the assailants carries a tree or a branched club as his weapon. Egil has already hastened out, bow in hand, and his three famous arrows have been shot. Above him is written in runes his name, wherefore there can be no doubt about his identity. The attack, according to Saxo, took place, in the night (noctuque nuptiis superveniens — Hist., p. 330). In a similar manner, Paulus Diaconus relates the story concerning Egil-Agelmund’s death (ch. 16). He is attacked, so it is stated, in the night time by Bulgarians, who slew him and carried away his only daughter. During a part of their history the Longobardians had the Bulgarians as neighbours, with whom they were on a war-footing. In the mythology it was “Borgarians,” that is to say, Borgar’s son Halfdan and his men, who slew Orvandel. In history the “Borgarians” have been changed into Bulgarians for the natural reason that accounts of wars fought with Bulgarians were preserved in the tradititions of the Longobardians. The very name Ebbo reappears also in the saga of the Longobardians. The brothers, under whose leadership the Longobardians are said to have emigrated from Scandinavia, are in Saxo (Hist., 418) called Aggo and Ebbo; in Origo Longobardorum, Ajo and Ybor; in Paulus (ch. 7),

|

|

Ajo and Ibor. Thus the namne Ebbo is another form for Ibor, the German Ebur, the Norse Jöfurr, “a wild boar.” The Ibor of the Longobard saga, the emigration leader, and Agelmund, the first king of the emigrants, in the mythology, and also in Saxo’s authorities, are one and the same person. The Longobardian emigration story, narrated in the form of history, thus has its root in the universal Teutonic emigration myth, which was connected with the enmity caused by Loke between the gods and the primeval artists — an enmity in which the latter allied themselves with the powers of frost, and, at the head of the Skilfing-Yngling tribes, gave the impetus to that migration southward which resulted in the populating of the Teutonic continent with tribes from South Scandia and Denmark (see Nos. 28, 32). Nor is the mythic hero Ibor forgotten in the German sagas. He is mentioned in Notker (about the year 1000) and in the Vilkinasaga. Notker simply mentions him in passing as a saga-hero well known at that time. He distinguishes between the real wild boar (Eber) roaming in the woods, and the Eber (Ebur) who “wears the swan-ring.” This is all he has to say of him. But, according to Volundarkvida, the mythological Ebur-Egil is married to a swanmaid, and, like his brother Volund, he wore a ring. The signification of the swan-rings was originally the same as that of Draupner: they were symbols of fertility, and were made and owned for this reason by the primeval artists of mythology, who, as we have seen, were the personified forces of growth in nature, and by their beloved or wives, the swan-maids, who represented |

|

the saps of vegetation, the bestowers of the mythic “mead” or “ale.” The swan-maid who loves Egil is, therefore, in Volundarkvida called Olrun, a parallel to the name Olgefion, as Groa, Orvandel’s wife, is called in Haustlaung (Younger Edda, i. 282). Saxo, too, has heard of the swan-rings, and says that from three swans singing in the air fell a cingulum inscribed with names down to King Fridlevus (Njord), which informed him where he was to find a youth who had been robbed by a giant, and whose liberation was a matter of great importance to Fridlevus. The context shows that the unnamed youth was in the mythology Fridlevus-Njord’s own son Frey, the lord of harvests, who had been robbed by the powers of frost. Accordingly, a swan-ring has co-operated in the mythology in restoring the fertility of the earth. In Vilkinasaga appears Villifer. The author of the saga says himself that this name is identical with Wild-Ebur, wild boar. Villifer, a splendid and noble-minded youth, wears on his arm a gold ring, and is the elder friend, protector, and saviour of Vidga Volundson. Of his family relations Vilkinasaga gives us no information, but the part it gives him to play finds its explanation in the myth, where Ebur is Volund’s brother Egil, and hence the uncle of his favourite Vidga. If we now take into consideration that in the German Orentel saga, which is based on the Svipdag-myth, the father of the hero is called Eigel (Egil), and his patron saint Wieland (Volund), and that in the archer, who in Saxo fights by the side of Anund-Volund against Halfdan, |

|

we have re-discovered Egil where we expected Orvandel; then we here find a whole chain of evidence that Ebur, Egil, and Orvandel are identical, and at the same time the links in this chain of evidence, taken as they are from the Icelandic poetry, and from Saxo, from England, Germany, and Italy, have demonstrated how widely spread among the Teutonic peoples was the myth about Orvandel-Egil, his famous brother Volund, and his no less celebrated son Svipdag. The result gained by the investigation is of the greatest importance for the restoration of the epic connection of the mythology. Hitherto the Volundarkvida with its hero has stood in the gallery of myths as an isolated torso with no trace of connection with the other myths and mythic sagas. Now, on the other hand, it appears, and as the investigation progresses it shall become more and more evident, that the Volund-myth belongs to the central timbers of the great epic of Teutonic mythology, and extends branches through it in all directions. In regard to Svipdag’s saga, the first result gained is that the mythology was not inclined to allow Volund’s sword, concealed in the lower world, to fall into the hands of a hero who was a stranger to the great artist and his plans. If Volund forged the sword for a purpose hostile to the gods, in order to avenge a wrong done him, or to elevate himself and his circle of kinsmen among the elves at the expense of the ruling gods, then his work was not done in vain. If Volund and his brothers are those Ivalde sons who, after having given the gods beautiful treasures, became offended on account of the decision |

|

which placed Sindre’s work, particularly Mjolner, higher than their own, then the mythology has also completely indemnified them in regard to this insult. Mjolner is broken by the sword of victory wielded by Volund’s nephew; Asgard trembles before the young elf, after he had received the incomparable weapon of his uncle; its gate is opened for him and other kinsmen of Volund, and the most beautiful woman of the world of gods becomes his wife. The mythology has handed down several names of the coast region near the Elivagar, where Orvandel-Egil and his kinsmen dwelt, while they still were the friends of the gods, and were an outpost active in the service against the frost-powers. That this coast region was a part of Alfheim, and the most northern part of this mythic land, appears already from the fact that Volund and his brothers are in Volundarkvida elf-princes, sons of a mythic “king.” The rule of the elf-princes must be referred to Alfheim for the same reason as we refer that of the Vans to Vanaheim, and that of the Asa-gods to Asgard. The part of Alfheim here in question, where Orvandel-Egil’s citadel was situated, was in the mythology called Ýdalir, Ýsetr (Grimnersmal, 5; Olaf Trygveson’s saga, ch. 21). This is also suggested by the fact that Ullr, elevated to the |

|

dignity of an Asa-god, he who is the son of Orvandel-Egil, and Svipdag’s brother (see No. 102), according to Grimnersmal, has his halls built in Ýdalir. Divine beings who did not originally belong to Asgard, but were adopted in Odin’s clan, and thus became full citizens within the bulwarks of the Asa-citadel, still retain possession of the land, realm, and halls, which is their udal and where they were reared. After he became a denizen in Asgard, Njord continued to own and to reside occasionally in the Vana-citadel Notatun beyond the western ocean (see Nos. 20, 93). Skade, as an asynje, continues to inhabit her father Thjasse’s halls in Thrymheim (Grimnersmal, 11). Vidar’s grass and brush-grown realm is not a part of Asgard, but is the large plain on which, in Ragnarok, Odin is to fall in combat with Fenrer (Grimnersmal, 17; see No. 39). When Ull is said to have his halls in Ydaler, this must be based on a similar reason, and Ydaler must be the land where he was reared and which he inherited after his father, the great archer. When Grimnersmal enumerates the homes of the gods, the series of them begins with Thrudheim, Thor’s realm, and next thereafter, and in connection with Alfheim, is mentioned Ydaler, presumably for the reason that Thor’s land and Orvandel-Egil’s were, as we have seen, most intimately connected in mythology.

|

|

Ýdalir means the “dales of the bow” or “of the bows.” Ýsetr is “the chalet of the bow” or “of the bows.” That the first part of these compound words is ýr, “a bow,” is proved by the way in which the local name Ýsetr can be applied in poetical paraphrases, where the bow-holding hand is called Ysetr. The names refer to the mythical rulers of the region, namely, the archer Ull and his father the archer Orvandel-Egil. The place has also been called Geirvadills setr, Geirvandills setr, which is explained by the fact that Orvandel’s father bore the epithet Geirvandel (Saxo, Hist., 135). Hakon Jarl, the ruler of northern Norway, is called (Fagurskinna, 37, 4) Geirvadills setrs Ullr, “the Ull of Geirvandel’s chalet,” a paraphrase in which we find the mythological association of Ull with the chalet which was owned by his father Orvandel and his grandfather Geirvandel. The Ydales were described as rich in gold. Ysetrs eldr is a paraphrase for gold. With this we must compare what Volund says (Volundarkvida, 14) of the wealth of gold in his and his kinsmen’s home. (See further, in regard to the same passage, Nos. 114 and 115.) In connection with its mention of the Ydales, Grimnersmal states that the gods gave Frey Alfheim as a tooth-gift. Tannfé (tooth-gift) was the name of a gift which was given (and in Iceland is still given) to a child when |

|

it gets its first tooth. The tender Frey is thus appointed by the gods as king over Alfheim, and chief of the elf-princes there, among whom Volund and Orvandel-Egil, judging from the mythic events themselves, must have been the foremost and most celebrated. It is also logically correct, from the standpoint of nature symbolism, that the god of growth and harvests receives the government of elves and primeval artists, the personified powers of culture. Through this arrangement of the gods, Volund and Orvandel become vassals under Njord and his son. In two passages in Saxo we read mythic accounts told as history, from which it appears that Njord selected a foster-father for his son, or let him be reared in a home under the care of two fosterers. In the one passage (Hist., 272) it is Fridlevus-Njord who selects Avo the archer as his son’s foster-father; in the other passage (Hist., 181) it is the tender Frotho, son of Fridlevus and future brother-in-law of Ericus-Svipdag, who receives Isulfus and Aggo as guardians. So far as the archer Avo is concerned, we have already met him above (see No. 108) in combat by the side of Anundus-Volund against one Halfdan. He is a parallel figure to the archer Toko, who likewise fights by the side of Anundus-Volund against Halfdan, and, as has already been shown, he is identical with the archer Orvandel-Egil. The name Aggo is borne by one of the leaders of the emigration of the Longobardians, brother of Ebbo-Ibor, in whom we have already discovered Orvandel-Egil. The name Isolfur, in the Old Norse poetic language, |

|

designates the bear (Younger Edda, i. 589; ii. 484). Vilkinasaga makes Ebbo (Wild-Ebur) appear in the guise of a bear when he is about to rescue Volund’s son Vidga from the captivity into which he had fallen. In his shield Ebbo has images of a wild boar and of a bear. As the wild boar refers to one of his names (Ebur), the image of the bear should refer to another (Isolfr). Under such circumstances there can be no doubt that Orvandel-Egil and one of his brothers, the one designated by the name Aggo (Ajo), be this Volund or Slagfin, were entrusted in the mythology with the duty of fostering the young Frey. Orvandel also assumes, as vassal under Njord, the place which foster-fathers held in relation to the natural fathers of their proteges. Frey, accordingly, is reared in Alfheim, and in the Ydales he is fostered by elf-princes belonging to a circle of brothers, among whom one, namely, Volund, is the most famous artist of mythology. His masterpiece, the sword of victory, in time proves to be superior to Sindre’s chief work, the hammer Mjolner. And as it is always Volund whom Saxo mentions by Orvandel-Egil’s side among his brothers (see No. 108), it is most reasonable to suppose that it is Volund, not Slagfin, who appears here under the name Aggo along with the great archer, and, like the latter, is entrusted with the fostering of Frey. It follows that Svipdag and Ull were Frey’s foster-brothers. Thus it is the duty of a foster-brother they perform when they go to rescue Frey from the power of giants, and when they, later, in the war between the Asas and Vans, take Frey’s side. This also throws |

|

additional light on Svipdag-Skirner’s words to Frey in Skirnersmal, 5: