|

THE STORY OF THE VOLSUNGS

There was a man called Sigi, and men said of him that he was a son of Odin. And Sigi was a mighty man, and of high kin. And it befell on a day that he fared to the hunting of the deer, and a thrall named Bredi fared with him. And at the end of the day, when they gathered their prey together, Bredi had slain more than Sigi. And Sigi was full wroth at this, and slew the thrall in his anger. And when the deed was known, Sigi was driven from his land. Arid he fared far away, and gat him ships and went a-warring. And ever did he prevail in his battles, and he won him lands and lordship. And he took a noble wife, and became a mighty king of a people called the Huns. And Sigi had a son called Rerir, and Rerir grew up comely and strong and a brave warrior like his father. And Sigi grew old, and his enemies, and some whom he deemed to be his friends, even the brothers |

|

of his wife, seeing that his strength had gone, came against him with a great host, and Sigi and all his folk fled. But Rerir, his son, had fared away at this time, and when he was told the tidings he vowed vengeance against his father’s slayers. And he brought together a mighty army, and won back his father’s lands and kingdom. Then did he wreak his vengeance upon Sigi’s murderers, slaying all those who had betrayed the old King’s trust in his time of weakness. And Rerir became a wealthy and a mighty King, wealthier and mightier even than Sigi. And he wedded a wife, and they loved each other dearly. But ill-content they were in that they had no children, and with great fervour did they pray the gods that a child might be born to them. And Odin heard their prayers, and a son was born, but Rerir never saw him for he was a-warring, and he fell sick, and came by his death. And the Queen died as her child was born. And the boy was called Volsung, and big and strong and daring was he from his earliest days, and the greatest of warriors did he become. And he wedded Ljod, the daughter of the giant Hrimnir, and they abode together in great love. Many children they had, and all were mighty and high-minded, but foremost and fairest beyond all were the two eldest, Sigmund their son, and Signy their daughter, and these two were twins. And King Volsung had built for him a great hall. Earls and men of high kin wrought it, earls’ wives wove |

|

the bright stuffs of its hangings, and queens’ daughters strewed its floors. Golden was its roof, and silver nails studded its doors. Hung upon its walls were the shields of the greatest warriors, and of these the least renowned was famed throughout the world. And in the middle of the great hall was a marvellous thing to see, for there stood a mighty tree whose branches reached to the roof, and wreathed it with the glorious garland of the year. And there the wild hawks dwelt, and they screamed above the heads of the drinkers of wine at the feast, and laughed when the swords were made ready for battle. And men called the tree the Branstock, and the throne of King Volsung was set there in the midst of a blossoming bower. And they dwelt together there, merry of heart, meeting good and evil days alike, and never forgetful of their gods. But even in those days of youth and hope, now and again there came a far-off murmur as of a threatening doom to the great Volsung, and here is now set down the beginning of that end foretold by the wise men of old. It was an even of May, and King Volsung sat in his great hall, and there sat with him his ten sons and Signy, his daughter, and many mighty men and fair women. And the feast was spread, and song and speech and laughter rang out around the board. When lo, there entered into the hall a man seeking King Volsung. And he hailed the King and told him that he was a messenger from Siggeir, the mighty King of the Goths. And Siggeir had heard of the beauty and wisdom |

|

of Signy, and he craved her for his wife, saying that in return he would give King Volsung his friendship and his aid in battle. And King Volsung and his sons were well pleased at this, for they fain would get to them more lands, and the King of the Goths was an exceeding mighty King. And they dreamed of themselves as kings of all the north, and even of far southern lands. And the messenger of King Siggeir stood before them bearing precious gifts, and gold and a ring, and other tokens of troth. And the snow-white Signy sat still, with folded hands upon her lap, gazing at him with wide, clear, dauntless eyes, that made the messenger’s heart grow cold. And King Volsung spoke and said: “Wilt thou be a great king’s wife, daughter, and bear great kings for thy sons, so that our name may never die?” And a hot flush spread over the whiteness of Signy’s face, and she answered with a voice that was as a cry: “E’en as thou say’st will I do.” And Volsung saw the fiery light in her face, and heard the cry, but nought did he understand of its meaning. But kindly and tenderly now he spoke, as one that loved her well, and would fain know her grief if grief there were. But Signy stretched forth her hand, and smiled upon him, and the flush faded from her face. “Would God it might otherwise be!” she said, and her voice was lowly and soft so that only he could hear, “Yet do I will to wed him.” Then in a louder voice she spake again and bade King Volsung be of good cheer, “for,” said she, “all |

|

well-counselled deeds of thine are fair and goodly, and those that are not so, have been willed by the mighty gods, and none may gainsay them. And, methinks, at my wedding there shall come a sign which shall bring joy to thy heart, whatsoever may follow after.”  And she sate again at the board, and King Volsung was fain to be content with her words. And he feasted the Goth-King’s messenger, and song and laughter and merry talk rang out as they passed the brimming wine-cup. And none heeded fair Signy as she sate wan and white, and her words of boding were forgotten in the mirth. |

|

And King Siggeir’s messenger fared back on the morrow, bearing gifts and gold, and a bidding from King Volsung that King Siggeir should come ere the summer passed and bear away his bride. So it befell on a midsummer eve that King Siggeir wended his way through the thicket in the glimmering twilight to the Volsung hall. Great was the company, and many the mighty earls that followed King Siggeir, and their chain-mail rang as they rode, and their spears and swords clanked in the stillness of the dying day. And as they drew near to the threshold of King Volsung’s hall, they saw how King Volsung himself stood amid the blossoms of his garden on the grassy sward, with five sons on either hand. And King Siggeir leapt from his horse and the two Kings hastened to meet. As the bramble to the oak was King Siggeir by the side of the glorious Volsung, nor did his helmet reach to the shoulder of even the least of Volsung’s sons. And they entered the hall, and the board was spread, and far into the night they feasted and drank the bright wine. And Signy was told the tidings, and close she kept in her bower; there she sat and strove within herself, watching wide-eyed the death of the day, and the passing of the moon-bright hours, and the birth of the morn which should make her the wife of the Goth-King. And when the sun was high they led her forth, a glorious bride to the bridal. And the feast was spread, and she sat beside her lord. No word did she speak, and no smile came to her lips, and cold and hard were |

the eyes which now and again she turned side-long on the Goth-King. And Sigmund, her twin-brother, looked upon her with a great fear in his heart, and he watched her till their eyes met. And at what he saw hatred awoke in him against King Siggeir, and he would have stayed the bridal but for the plighted word of the Volsungs. And Siggeir saw the glances of the brother and sister, and well he understood their meaning yet he made no sign, but bided his time. And King Volsung saw nought but laughed aloud with King Siggeir in the content of his heart dreaming of glories to come when his kindred should rule the world. So they feasted and sang and told old tales when lo, over the cloudless blue of noon-day, a long deep roll of thunder passed, and to some it seemed that it was a man that laughed out. And they looked around them and turned to the door, and in that moment there strode into the hall a mighty man. One-eyed he was and seeming old, yet was his form erect and his visage bright. Grey as the stormy sky was his kirtle, and cloudy blue was the hood which was drawn over his |

|

head, and both were fashioned as was the raiment of men of old. None gave greeting to him, and no greeting did he give to any, but strode to the Branstock and drew from the grey folds of his garment a great gleaming sword. And he thrust the sword into the trunk of the huge oak, while the wild hawks screamed and laughed over his head. Then at last he spoke: “Earls of the Goths and Volsungs,” he cried. “Lo, in the Branstock a worthy sword. Whoso draweth the sword from the stock shall e’en take it as a gift from me, and never shall it fail him except his own heart falter. All hail to thee, King Volsung! Farewell for a little while!” No man moved as he spoke, for his voice was as music in their ears, and they sat as in a happy dream, dreading awakening. And slowly down the hall floor and out at the door did the stranger pass, and none stayed him or cast at him a question, for well they deemed that the sword was Odin’s gift. And at last King Volsung broke the silence and bade the Volsungs and the Goths set their hands to the hilt, and see who was the warrior fated to take it for his own. And King Siggeir, deeming it an easy task, and that he would have the best chance who should first lay hand to the sword, asked King Volsung that he might be the first of all men in the trial. And King Volsung answered: “Herein, I ween, is the first as the last, for as the gods have willed so shall it be; yet, O guest, begin.” And King Siggeir went to the tree, and put his hand to the golden hilt, and strained with all his might |

to draw the sword forth. Yet was it as firm as ever in the Branstock. And his heart was black with envy and hatred as he wended his way back to his seat, and never a word he spake. And a hot flush burnt on the pale cheek of Signy, as Siggeir sat him down beside her, and her heart was nigh to bursting with shame of the man that was now her lord. And now did King Volsung bid all the followers of King Siggeir make their trial, and each upstood in his turn, and mighty warriors were they all, who had done many wondrous deeds on the battle-field. Yet did not the sword in the Branstock move for any of them. And now did the Volsung home-men and shepherds, hunters and sea-farers, gather round the oak to try their strength, and deft though they were in labour, in vain did they pull at the sword. And next did King Volsung lay his hand to the hilt, and he drew and strained, but in nowise could he move it. Yet did his mirth not forsake him in his failure. Laughing, he wended his way back to the high seat, and called upon his sons to stand forth and try their skill. And the ten uprose and stood about the tree, and from the youngest upwards did they put |

|

their hands to the fateful sword till nine had tried and failed. Then Sigmund drew near, and caught the bright hilt in careless fashion, as though he deemed the trial all for nought. But lo, aloft in his hand shone out the glittering naked blade, drawn from the heart of the oak as easily as if it had lain all loosely there. And in triumph Sigmund shook it over his head while a great shout went up from all the Volsungs and the Goths. Right glorious was Sigmund then to look upon, a king over kings. And with the sword still in his hand he betook him slowly to his seat. Sober now was his face, for he deemed that there was some great work that Odin would have him do. And he lifted his eyes to Heaven as the solemn thoughts stirred within him, thoughts of dread and of longing both of the hour when the gods would use him for their will. And as his eyes fell they met King Siggeir’s smiling and blithe. And King Siggeir spake unto him and said: “Seeing that the sword came to my wedding, methinks it is fit that it shall be mine, O best of the sons of the Volsungs.” And he offered Sigmund gold and silver, gems and precious stuffs as much as he would, but Sigmund laughed and answered: “Thou mightest have taken the sword no less than I, if it had been thy lot to bear it, but now since it has fallen to my hand, I will hold it, though thou biddest therefor all the gold thou hast.” And Siggeir was wroth at the answer of Sigmund, for he deemed that he had scorned him, but he made no sign, and hid his wrath with a smile. But full were his thoughts of hatred and revenge. |

|

And the next day, the weather being fair, King Siggeir made known his will to set out for Gothland, lest, as he said, the wind should rise and the sea become impassable. And King Volsung besought him to stay longer, for this short feasting at a marriage was not according to the wont of men. Yet in nowise would Siggeir consent. But he bade King Volsung and his sons and all the mighty men of the Volsungs journey to Gothland before the summer was over, and abide there through the winter. And King Volsung thanked him and answered “No king might scorn such a bidding, Siggeir: surely will I come.” And the matter was settled that on the morrow King Siggeir and Signy should sail for their Gothland home. And that night the feast was braver than before, and song and laughter and speech rang out till, late in the undark night, the feasters went to slumber. But Sigmund was heavy of heart, and Signy lay on her pillow, full of boding for the days to come. And wise was Signy and many a thing she knew of future hap. And in the silence of the midnight she knew the doom that was coming upon her and her Volsung kin. And she stole from her bed and crept to the chamber of King Volsung. And he sat up and kissed her, and bade her speak what had brought her there. And she said: “Hearken, O my father, and when the morning cometh, think upon my words. Let me go forth with King Siggeir, but do ye abide in this land, nor trust the guileful heart of the Goth-King, lest the kin of the Volsungs shall perish.” |

|

And King Volsung smiled upon her, and held her close as when she was a child. “My word is given,” he said. “To death or to life must I wend when the time shall come, but this will I give to thee, that thy brothers shall not wend with me.” Then did she cling to him, and swiftly cry: “Nay, but if thou goest, have thy sons with thee, and a host and a mighty company. Meet thou the guile and the death-snare with battle shout, and with blood-drenched sword.” “Nay,” said he gently, “my troth-word is e’en plighted, and I must go as a guest as my word was.” And Signy wept upon his bosom, but nought more would she say to turn him from his purpose. And back she wended to her pillow and lay there, wan and open-eyed, till the dawn broke, and the sun shone out on the Volsung hall. And the silence of the darkness ended, and now was heard the stir of the departing folk as they arrayed them for their journey. And when King Volsung entered the hall, there stood Signy by the Branstock, clad for faring, with the earls of the Goths around her. Queenly and calm she stood, with the flush of youth and loveliness upon her cheek. And King Volsung looked upon her, and deemed that the happenings of the night were but a vision in his slumber. And he was fain to be content, though sad was the parting. And down they rode to the sea, and there stood the ships ready for sailing. And Signy kissed her brothers, and then she hung awhile about her father’s neck and kissed him many times, and whispered fond |

|

parting words that none other might hear, and none may tell. And King Siggeir left the Volsungs with fair words and blessings on his lips, while his heart was full bitter towards them. And the horn sounded, and Signy was borne away from her kin and the land she loved. And she bowed her head, not trusting herself again to look upon them. And the Goth lords gazed at her pityingly, and none there was but blessed her from all harm.  Now, when two months were well-nigh past, King Volsung called his sons and his men of counsel to him, and then did he tell them of Signy and her words of warning. “Now, not over much will I hold her word,” said he, “nor will I doubt it, for Signy is wise among women. But this now will I do. In peace will I go to King Siggeir’s bidding, but ye, my sons, shall tarry |

|

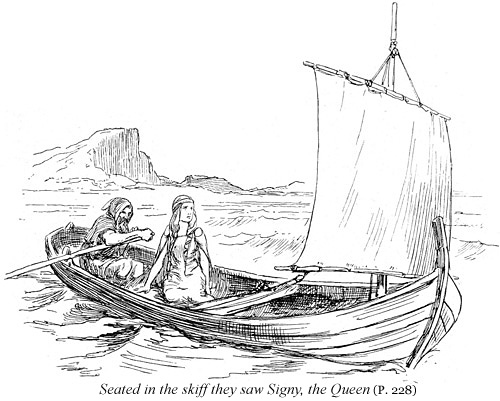

in this land and keep the realm for me, lest our race shall come to nought.” But with one voice they answered that they would go with him, and take honour, or fall beside him as the gods should will. Then said King Volsung: “So be it; we will go together, a band of friends, and if the worst betide, the gods must e’en look to our land and people.” And they arrayed three ships, and King Volsung went aboard with all his sons and a goodly company. And on a day, at eventide, they drew near to the shore of the Gothland. And a little skiff with a grey sail put out to meet them. And seated in the skiff they saw Signy, the Queen. And she came aboard the King’s vessel, and her pale face lighted up with joy as she looked again upon the well-loved Volsung faces. And she held her father long in her arms, and kissed her brothers with warm, quivering lips. “O strange!” she cried, “O sweet, the well-known ships to see!” Then did she speak again in hasty words, telling of the purpose of her coming. “Short is the time,” she said, “for telling that which I would tell. But that which I spoke aforetime as a boding of my heart is even now a truth. Siggeir hath prepared to war against you. The death-snare is laid. But fair winds have wafted you to our shores ere the time appointed, and Siggeir looks not to meet you yet. O my father, O my brethren, I pray you to turn back ere it be too late. Take me with you, my father, to my own dear land again.” Then did King Volsung strain her to his breast |

|

and kiss her pale cheeks and brow again and again, seeking to give her the comfort that his words could not give. “Never yet,” he said, full gently, “have I turned me backward from my word. Wouldst thou have me do it now? And look thou upon thy brethren. Are they not goodly and great? Wouldst thou have them mocked at the feast that they feared the sword of Siggeir?” Then did Signy weep, crying: “Let me, then, bide death with thee and them!” But he bade her return and take her fate from the hands of the gods, remembering ever the love wherewith they loved her. Quietly then she kissed them again, and fared back in the gathering darkness. And she sat beside King Siggeir at the board, and grim was the side-long gaze that he turned upon her, and well he guessed the deed which she had done. And on the morrow when the sun shone out over land and sea, King Volsung and his company went ashore, and wended their way towards the dwelling of the Goth-King. And they came to the top of a grassy hill, and lo, they saw below them a great army gathered and their shields and spears glittered in the brilliant sunshine. And King Volsung bade his people halt and array themselves for battle. And shield to shield they placed, and drew their swords from their sheaths. Glorious was the glint of the gold, and glorious their forms, and the light upon their faces, as they turned them to the approaching foe, but more glorious than all stood Volsung the King in the very front of his people, his |

|

|

|

visage calm and lovely as he awaited his doom. And he drew his sword, and cast the sheath from him, and raised the gleaming blade to Heaven. And up from the valley carne the foe, shaking the earth with their might, but sounding no battle cry. And the Volsungs, too, were silent. Then at last the Goth-folk fell upon them, and many times were they driven back from the Volsung wall of shields. Thereafter, when many a mighty man had dropped to earth, the wall was broken, and fierce then raged the fight within it. And King Volsung stood still in the place which had been the forefront of the battle, and watched across a line of corpses the long struggle. Then at last did the throng of spears press near and close around him. And he threw his blunted sword among the crowding foemen, and flung his shield far from him, and stood awaiting the onslaught of the weapons. And thrust back by the spears which clashed amid his breast, with body rent and torn, he fell with a ringing thud upon the dead men’s shields. And none of his foes durst look upon him dead for it seemed as if a god had fallen, and they feared the wrath of Heaven. And they took the sons of Volsung, sore, wounded, and hound them, and carried them before Siggeir. And they told him the tale of the fall of Kin, Volsung, for Siggeir had not come into the battle. And when Queen Signy heard the tidings she hastened to the hall, and stood before the King as he sat in his high seat, flushed with his triumph. Wan and white, but tearless, Signy stood, and prayed that |

|

her brethren might live, if only for a day or two, before he gave them to death. Then spake Siggeir, commanding that the Volsung men be taken into the forest and there fettered to a mighty beam. “There,” said he, “shall they live till Queen Signy come again and pray me for their death.” And as Siggeir bade so was it done. And the days and nights passed, and each day was the tale brought how wild beasts had eaten the brothers one by one, till only Sigmund was left. And each day Signy watched and waited, hoping to carry succour to her brethren, but so well guarded she was that she might not stir from her dwelling. And well-nigh mad was she for woe, and her heart was as a flame in her bosom. And the next day she strove no more to depart from the watching eyes, but sat in the high seat, looking at none and speaking to none. And the darkness came, yet she stirred not, and to Siggeir’s messengers she gave no heed, but still sat on alone, wan and cold and unmoved. And when the morning came, Siggeir entered the hall with his men of counsel, and he sat him down beside her on the high seat. And the woodman came unto Siggeir and told that no man now was left on the oaken beam, but only bones, and the bonds that had once bound the Volsungs. And a sudden wail rang out from Signy, and she stood up, and thrust all people from her, and fled, fleet of foot from the hall to her bower. And her maidens were frightened at her wild glances and the strangeness of her face, and they ran from her. |

|

And there she sat in silence till the night fell; then did she arise and fare forth alone in the darkness, but none hindered her, for they deemed the story of the Volsung race was done. And on she went till she came to the forest, and there she took to a trodden way which she guessed had been made by the messengers of King Siggeir. And she followed it by the light of the moon till she saw before her a wide sward. And lo, in its midst stood a mighty man, who threw up the earth with a great branch which he had torn from a tree. And she looked but once, and knew that it was her brother, Sigmund the Volsung, and she cried out his name and ran to him. And she saw that his raiment was foul and torn, and his eyes great and hollow and wild as those of a famished man. And joyfully he hailed her, saying how he had looked for her each day, but that he had guessed her plight when she came not to the aid of her brethren. “This labour of mine,” he said, “is to bury the bones of the Volsungs, and well-nigh is it done. Draw near, thou daughter of Volsung, and pile with me the stones upon these goodly sons.” And the white-handed Signy toiled with him through the night until the task was done. Then did she seat herself upon a fallen tree, and draw him down beside her. And she said: “Now shalt thou tell me the tale of how our Volsung brethren met their end, and then will I wend my way back to King Siggeir’s dwelling, sick-hearted and sorrowful for them and for thee.” And Sigmund told her of the coming of the wolves |

|

each night, and of the deaths of his brethren, and of his own escape. “I, Sigmund the Volsung,” he cried, “who have borne the sword among the kings of men, in my fury and flaming wrath, I became wolfish too. And I snarled to the she-wolfs snarling, and snapped with teeth as greedy as hers. I caught her with my teeth, and with her writhing, the bonds that bound my hands burst, and I smote the beast and caught her by the throat, and held her till she fell dead.  And I hid in the thicket till the morning and then came Siggeir’s watchers. And I looked upon them from my hiding-place, and fain I was to slay them, but I deemed it wiser to let them go. But hereafter, because of my childhood’s days, and my father’s precious love, shall there come a time when nought shall hinder or turn back this hand of mine from the slayers of the Volsungs; yea, though a swordless outcast, a hunted beast of the forest I may bide, as well I may, long years of waiting.” |

|

Wild were his eyes, and aflame with ruthless hate was his face, as he foretold the doom of the Goth-King, and Signy listened, white and calm and motionless, as though she were wrought of stone. But when he had finished, she rose and stood before him with kindling eyes that shone like stars in the grey dawn. “My brother,” she said, “strong thou art and wise, and the day shall surely come when the Goth-King shall pay for his treacherous work, and surely shall I live to see it. But the heavy burden of thy wrath shall pass away, and thou shalt live a glorious King, and all men shall tell of thy deeds. Never again, O brother, shalt thou be alone in thy waiting; make thee a dwelling in the wild wood, and ere many days I will come to thee again, and bring thee help and comfort.” And she kissed him and left him, and returned to the King’s dwelling, as the morning sun shone out. And quietly now did she bend her to the will of King Siggeir. Nought was there in her pale lovely face to tell of the raging fire within her breast, and nought in the calm gaze of her gentle eyes to tell of her constant watching and patient waiting for the day of vengeance. And never a word she spake when Siggeir took to himself Odin’s sword which Sigmund had wrenched from the Branstock, or when he sent his mightiest men to seize the dear Volsung land. And when a half month had worn away, again did Signy wend her way to the wild wood. There by the river, in the heart of the thicket, she saw Sigmund again. And her heart leapt as she beheld him, so mighty and fair was he, and she said within herself |

|

that once more had she looked upon a man. And Sigmund greeted her with joy, but his words were few, for none did he see to speak with, and ever did his thoughts dwell on sorrow and vengeance. Yet were the few words he spoke to Signy full of love, and her sad heart was gladdened by the sound of his voice and the sight of his face. And he showed her his dwelling-place, a strong cave well hidden in the thicket, and washed by the river’s wave. And when it was time to part, Signy held him close and wept, for she deemed that never again might she see this last of her kindred. And she wended her way back to the hall of Siggeir, and men say that never again did she weep or smile. Lovely as ever was her face to all men, but never again did it change for fear, or longing, or pity. It was as though her heart were dead within her living body. And the years passed by, and Sigmund lived on in the forest, gathering to him the wherewithal for his vengeance in the future. Sometimes he fell upon mighty earls of the Gothland as they journeyed through the forest. Then would he take their war-gear and their gold, and these he would store for the coming day. And he set up a forge, and made himself a master in the smithy’s craft. And hunters saw the light of his fire in the darkness, and the fishers heard the ring of his hammer, and folk said among themselves that a giant had awakened in the forest, and it were well to keep out of his hands. And all memory of the Volsungs and their doom passed from the minds of the people, and Sigmund worked on and waited. |

|

Now, when some ten summers had passed, it befell on a day that Sigmund sat on the green sward outside his dwelling, fashioning a golden sword. And along the banks, on the other side of the river, came a maiden, leading a child, a boy of some ten summers old. And when she saw Sigmund she hastened towards him and cried: “O forest dweller! harm us not, we bear thee a word from Signy, the Queen. And thus does she say to thee: “I send thee a man to foster if he be strong of heart, he may help thee in thy need, but if he be weak of heart, weary not thyself with such as he, but let him wend his ways to his fate.” And when she had thus spoken, the maiden turned and left him, and the child stood there alone, smiling and fair and well content. And Sigmund saw the meaning of Signy’s words, how that she would send him a helper in his vengeance, but that she doubted the courage of any son of Siggeir’s. He knew, too, that Signy would have him slay the child, if it should prove that he followed after the Goth-King and had not the Volsung heart. And Sigmund rose and crossed the river and took the boy on his shoulder. And he bade him hold his sword, and then he plunged into the rushing river, and waded across, thinking to try the child’s courage at once. But the boy heeded not the foaming water as he sat on Sigmund’s shoulder, but prattled of this and that and questioned him of all he saw. And Sigmund deemed that he was bold of heart. And for three months the boy lived the hard, simple life in the woods, |

|

and strong he grew and skilful, and now was Sigmund minded to put his courage again to trial. So on a morn he called the boy to him and said: “I go to the hunt: bide thou here and bake the bread whiles I bring the venison.” And he returned at noon with the flesh and said: “Is the morn’s work done?” And the boy answered not for a space, and Sigmund looked upon him and his face was white and fearful. Then said the lad: “I went to the meal-sack, and something there was within it that moved, and methought ’twas a serpent, and I feared, and durst not open the bag again.” And Sigmund laughed aloud, and went to the meal-sack and thrust in his hand, and drew out a deadly adder, and he went to the door of the cave and threw it from him into the grass. And he came hack to the boy and drew his sword and cried: “Dost thou fear this, O Son of the Goth-King, that men call the serpent of death?” And the boy answered: “I am yet young for the fight, but such a blade shall I carry ere long.” And Sigmund went out into the night and leaned long upon his sword, and thought of the words of Signy. And many an hour he stood there, but at last he sheathed his sword and went to the door of the cave, and called: “Come forth, King Siggeir’s son.” And the boy came, and he looked into Sigmund’s face and trembled. And Sigmund bade him follow him, and he led him through the wood till they came to that spot where his brethren lay buried. And there Sigmund lingered awhile, looking upon the fair June blossoms |

|

which clustered about the place. And then they went on again, till they came to the edge of the forest, and there Sigmund stayed him and said: “King Siggeir’s son, no longer will I foster thee. Get thee to the house of the Goth-King and find thou Signy, the Queen, and say unto her the word, “Mother, I come from the forest, and he who hath fostered me saith that the sons of the gods may help him, but never the sons of kings.” And Sigmund turned and strode back to his dwelling, and the boy went on till he reached the hall of Siggeir, the Goth-King. And he sought Signy, the Queen, and spake unto her the words of Sigmund. And Signy hearkened to him, and long she pondered the words, and sad she was at the failing of her hopes. And it befell that when some months had passed away that another son was born to Signy. And the child was a Volsung to the heart from his earliest days, and Signy watched him carefully and tended him wisely. And lo, when ten more years had passed away, Sigmund sat on a day by his stony dwelling and wrought a helmet of gold. And on a sudden a voice called to him from the other side of the river. And the voice said: “Thou surely art the dweller in the wood of whom my mother spake.” And Sigmund looked up and beheld a boy of some ten summers. Fair he was and strong, with eager, fearless eyes that fell not before the stern gaze that Sigmund cast upon him. And the boy flung himself into the rushing water, and past his chin it rose, but he heeded it not, but struck out with strong stroke till he reached the shore |

|

where Sigmund stood. And he came to him, and looked up at him wonderingly. And the Volsung laughed and said: “Thou runnest to me as fast as others run from me; what wouldst thou, son of a king?”  And the boy answered: “Wondrous it is: here is the cave and the river, and all that my mother spake of. Yet did she say that none might behold thee without fear, but I fear thee not.” |

|

Then said Sigmund: “And by that token only shalt thou live with me. But tell me thy name, and thy years, and the words of Signy, thy mother.” “Sinfiotli is my name,” said the boy, “and ten summers have I seen, and this is the word which I bear from Signy, the Queen: That once more she sendeth thee a man-child to foster, but whether he be of the kings or the gods time shall show thee.” And the heart of Sigmund yearned unto the lad, but he thrust the thought of love from him, saying to himself that this, too, was Siggeir’s son, and would doubtless fail him as the first had done. But he took the boy to live with him, and he tried him with weary and dangerous tasks, and Sinfiotli bore all well. Hardy he grew, fierce of heart, and cunning of hand. And on a day Sigmund said unto him: “I will wend to the hunting of deer; do thou bide here and bake the bread against my coming.” And he went and returned, and the boy met him as ever, glad of his coming back. “Hast thou kneaded the meal?” asked Sigurd. And Sinfiotli answered “Yea, but hearken to a wonder. When I would handle the meal, something moved in the bag; but since we must needs have bread, I kneaded it all together, and the wonder is baked in the bread.” And Sigmund laughed aloud at the boy and said “Thou hast kneaded into the bread the deadliest of all adders, so eat not to-night, or thy death will come of it.” And full glad was Sigmund and no longer did he stifle his love towards Sinfiotli. And he taught him all deeds of the sword and feats of war. And in three |

|

years a mightier warrior was he than any full-grown man. And through good and evil days did they abide together, and ever greater and greater grew the love between them. And it befell on a day that Sinfiotli said unto Sigmund: “Methinks there was a lesson for me to learn, and a lesson that thou hadst to teach, and therefore was it that I left the dwelling of the Goth-King. Teach me then, O master, what thou wouldst have me to do.” And Sigmund looked at the lad, and dark and grim was his face, and his eyes blazed with a strange light. And he answered Sinfiotli: “Behold, this is the deed thou must do; we twain shall slay my foe; and what if that foe were thy father?” And never a word spoke Sinfiotli. But he fixed his eager eyes on Sigmund, and his breath came fast and short, as Sigmund told him the story of the slaying of the Volsungs. And when it was told, Sinfiotli laughed out aloud, and said: “Well wot I that Queen Signy is my mother, and her will I help at her need, but never has King Siggeir been father to me: never gave he me a blessing but many a curse. No father have I but thou, who hast cherished me and taught me and loved me these many years. Lo, here is my hand ready to strike where thou wilt. I am the sword of the gods; do thou, O my father, hold the hilt.” Joyful was Sigmund at the words of Sinfiotli, and fierce glowed his eyes and hot his cheeks at the thought of his long-waited vengeance so nigh. And the twain talked together of the time which should best serve them and of the manner of their vengeance. |

|

And at last when the winter drew on and the nights were long and dark, they fared unto Siggeir’s dwelling and hid them in a bower beside the great hall where the King’s wine-casks were kept. And so near were they that they saw the light of the torches, and heard the mirth of the feasters. And calm was Sigmund and his eyes clear and bright, but Sinfiotli was haggard and white, and he bit at the rim of his shield and fretted for the fight to begin. Now, it befell that two little children, the youngest born of Queen Signy, played about the hall, trundling a golden toy. And a ring fell from the toy and rolled away into the bower and lay at Sigmund’s feet. And the children followed it, and came face to face with the strangers, all glorious in their shining armour. Then they fled before they could hold them, back into the hall. And they cried out what they had seen, and on a sudden all was din and tumult. And Sigmund and Sinfiotli sprang to their feet and stood ready with their weapons, resolved to strike with all their might ere they should die. And as they thus stood, lo, Signy came to them, and fierce was the light in her eyes at their betrayal by her babes, and she looked into Sigmund’s face and wondered at its calmness. “Thou smilest, and thy eyes are joyful and clear,” she cried, “yet the end is come.” And now the clash of arms and the hurry of feet came nigh them, and Signy was swept aside in the throng of the Goth folk. And in the midst of the naked blades stood Sigmund as firm and unbending as is the great oak in the forest to the herd-boy’s |

|

assaults. But Sinfiotli rushed hither and thither wherever the spears were thickest, and fiercely he laid about him till at last he slipped and fell. Then thicker came the throng about Sigmund, and they bore him down unwounded, and cast bonds about him. And Sinfiotli, too, did they bind, and they carried them away. And when the morning dawned King Siggeir bade his bondsmen make an earthen mound, and divide it by a great stone into two chambers. And when it was done, they brought Sigmund and Sinfiotli to the mound, and put one into each chamber. Then did they begin to roof in the chambers with turfs. And at the eve of the day all was done but the roofing of Sinfiotli’s chamber. Then came Signy, the Queen, all white, and wan, and great-eyed. And she gave gold to the thralls and bade them hold their peace of the deed she was about to do. And she drew forth from beneath her mantle something wrapped in straw, and swiftly she cast it into Sinfiotli’s chamber. And then she fled away into the King’s dwelling. And the thralls deemed that it was food that she had brought to Sinfiotli, and they laid the roof on his chamber, and left the two men to their doom. And Sigmund listened, and he heard Sinfiotli speak and say: “Behold, my mother hath sent me meat.” And then there was silence, and Sigmund called to him: “Hath aught happened to thee? Is there an adder in the meat?” And Sinfiotli laughed aloud and answered: “Yea, indeed, an adder; the sword of the Branstock.” |

|

And Sinfiotli smote the stone wall with the point of the sword, and slowly in the darkness he bore through the wall, till Sigmund could set his hand to the blade on the other side. Then they sawed together till the stone was cleft and they looked upon each other again. And full of joy they kissed, and again they sawed at the roof of their prison till the winter stars shone down upon them. Then out they leapt, and straight for the hall they made. And they slew the night-watch one and all. And they took the faggots which were stored for the winter, the cloven oak trees, and the ash and the rowan, and made a mighty pile around the dwelling of Siggeir. And they laid a torch to it, and watched till the flames rose high above them. Then they drew their swords and stood one at each of the two doors, that none might escape. And Siggeir awoke and saw the great fire all around him, and he cried out that he would give all his heaped-up treasure and half of his kingdom if his life might be spared. And Sigmund answered him and cried in a loud voice: “No treasure do we seek or kingdom, but vengeance for our kin. Nought can buy thy life, O Siggeir! death now shalt thou take from the hands of those whom thou wouldst have done to death.” And a great fear entered the hearts of all who heard him, and the silence of dread fell upon them. And again the voice cried aloud: “Come forth, ye women of the Goth-folk, and go your ways; and thou, Signy, my sister, come forth, that once more we may dwell in peace together beneath the Branstock.” And forth came all the women, hurrying in terror, |

|

and Sinfiotli lowered his sword and let them pass, but Signy was not amongst them. Then the men rushed to the doors and sought to pass, but Sigmund and Sinfiotli drove them back into the flames. And now came Signy to the women’s doorway, clad in queenly raiment, and Sinfiotli lowered his sword point before her. And she folded him in her arms and kissed him, praising him for his mighty deeds. And she bade him farewell and departed and came unto Sigmund. And he looked upon her face, and he deemed. it fair and fresh as in the days of their youth long past, but as he gazed, the tears filled her eyes, and sobs shook her breast. And she said: “I have come but to greet thee, Sigmund, then back again will I wend and meet death with my husband, the Goth-King. Yet fear not that I shall forget thee. A mighty king in the Volsung land shalt thou be, and then shalt thou remember me and my love of the Volsung name. Happy was my youth with my kin, loathed since has been my life, yet now as it endeth, softened seems my heart, and I would not that it had been otherwise; only I long for rest.” And softly and sweetly she clung about him and kissed him, murmuring: “Farewell, my brother.” Then she turned her back and passed from his sight, and never again did he behold her. And the walls of the great hall crashed and fell, and when the sun rose high nought but ashes remained of the golden dwelling, and the ashes of Siggeir and Signy and all their mighty men were mingled in its ruin And Sigmund and Sinfiotli gathered a mighty host |

|

together and sailed from the Gothland to the land of the Volsungs. And there the people met them with joy, and once more did the Volsungs rule beneath the Branstock’s boughs. And oft did Sigmund think of Signy, and oft did he tell of her life and fame, and her love of the Volsung people, and her noble death. And Sigmund became a mighty king, and he wedded a fair and lovely wife, named Borghild. And it befell that through her Sinfiotli came to his end. And in this wise was it. There was a man named Gudrod, and he was the brother of Borghild. And he broke troth with Sinfiotli in a certain matter, so that they quarrelled and fought, and Sinfiotli slew Gudrod. And when the deed was known, Borghild bade Sigmund send Sinfiotli from his kingdom, but Sigmund answered her that Gudrod had broken troth with Sinfiotli and therefore was to blame; but for atonement he gave unto Borghild much gold and precious gems. And Borghild made as though she was satisfied, but in her heart was she full of hate to Sinfiotli. And on a day she made a funeral feast for Gudrod. And mid the feasting she gave to Sinfiotli in seeming good-will a cup of wine. And it was poisoned, and he drank and fell dead without a word or groan. And Sigmund ran to him with a great cry, and he sorrowed over him exceedingly, so that none durst come to him. And he gazed long upon him, and took the body in his arms and ran forth from the hall. And the wind was wild and the night dark with storm-clouds, but on he went till he came to a mighty water. And lo, as the morning dawned there came a white-sailed boat to |

|

the shore, and in it a man, mighty, grey-clad, one-eyed, and seeming old. And he hailed Sigmund and asked him whither he fared. And Sigmund answered that he would cross the water and seek a new life, for the light of his old life had gone. And the man looked up at Sigmund and said that he had been sent there to fetch a great king, and he bade Sigmund set his burden upon the ship. And lo, when Sigmund had done this, and would have followed into the boat, both man and boat had disappeared. And long hours did Sigmund stand upon the shore, gazing out on the water. Then he turned and made his way back to the Volsung land. And he sent Borghild the Queen from him, and for long he lived alone. Now, there was a king of the islands named Eylimi. Small was his kingdom, but wise and valiant was he. And he had one only daughter, named Hiordis, and exceeding wise she was and fair, and her fame reached Sigmund and he was fain to have her for his wife. And he sent one of his earls to King Eylimi with gifts and tokens, asking Hiordis in marriage. And King Eylimi knew not what to say, for that very day had come an earl from King Lyngi, and he, too, would wed Hiordis. And Eylimi thought how Sigmund was growing old and his realm was afar off, while Lyngi was young and eager for fight, and a mighty king, and his realm was nigh; therefore did Eylimi fear to make a foe of him. So he went to Hiordis where she sat in her bower, |

|

working in silk and gold the stories of the deeds of old, and the stories of the deeds to come. And he told her of the two kings, and of his fears should she deny King Lyngi, but he bade her choose, saying that her will should rule in the matter. And Hiordis straightway answered him: “Well I wot that strife may come of this, yet can I give but one answer. King Sigmund will I wed, and deem it the crown of my life to live in the Volsung land and share with him strife and peace.” And fearful was Eylimi as to what might come of it, but in nowise would he gainsay the word of Hiordis. But he sent rich gifts to King Lyngi and a message that Hiordis had plighted her troth to King Sigmund. And to King Sigmund he sent bidding him come with all speed for his bride, and to come with a goodly company, arrayed for war, lest evil should betide. And right contented was Sigmund at the message, and he made him ready. Yet did he ponder the word of King Eylimi that he should come in war array, and it suited not with his joy. And he remembered his father, and how he scorned to go to the court of King Siggeir with a war-host. So Sigmund gathered to him the best of his mighty men, and splendid was their raiment, and of precious metals were their shields and weapons. And they went aboard ten longships. Nought more would he take with him than he deemed would do honour to the Volsungs and to the fair and wise Hiordis. And they came to Eylimi’s kingdom, and a goodly |

|

welcome awaited them. And Sigmund looked on Hiordis and loved her exceedingly, and right happy was Hiordis when she looked on the glorious King. And Eylimi made a great feast, and Sigmund and Hiordis were wedded. And day by day did they love each other more, and ever their joy grew. And Eylimi was glad in Sigmund, and he forgot his fear of King Lyngi. And when more than a month had passed, they arrayed the ships to return to the Volsung land. And lo, tidings came that a great host and many ships lay off the coast waiting for battle. Then was King Eylimi sore afraid, but Sigmund comforted him and bade him go forth with him to the fight, and take whatever the gods should give. And Sigmund drew the sword of Odin from its sheath, and he and Eylimi led their men down to the sea strand. All golden did Sigmund shine in the noonday sun, and right glorious did all men deem him as they looked upon him. And he called upon them to fight well for the Volsungs, and he raised aloft the mighty sword of the Branstock and blew on his father’s horn the call to battle. And King Lyngi’s hosts rushed upon them, and surrounded them. But Sigmund slashed right and left with his mighty blade till the dead were piled around him, and none could get at him to smite him. His shield had been torn from his arm, and his helmet from his head. All white his hair streamed on the wind, and blood-stained and dust-covered was his raiment. But in his eyes was the light of victory, and he sang out sweet-voiced and clear the battle song of |

|

his kindred, and ever gleamed the bright sword as it struck its death-dealing blows. And just as he thought of triumph, lo, through the hedge of weapons came a mighty man. Seeming old he was, and one-eyed, and his face was as a flame. His kirtle was of the grey of the clouds, and his hood of misty blue. And he bore a great two-handed bill, and when he had come to Sigmund, he raised it to strike him. Then once more the gleaming sword of Odin circled around the head of Sigmund, and he shouted again the war cry of the Volsungs. But as his sword met the bill, it shivered to pieces, and fell from his hand. And when Sigmund looked again the grey-clad man had vanished, and in his place thronged his foes. Weaponless, unshielded, unhelmed, the war-light gone from his eyes, he stood before them. And there they smote him, and he fell upon the heap of the dead, whom he had himself smitten down. And now that their King was fallen his men struggled no longer against the oncoming host, and they fell before them. And right well fought King Eylimi in the forefront of the battle, but he, too, fell. Now did King Lyngi fare to the dwelling of King Eylimi to seek Hiordis and to take her by force. But she had left her bower when the fight began and hidden in a thicket, whence she could watch the battle. And she saw the triumph of King Lyngi, and beheld him as he rushed from the field towards their dwelling. And she guessed that he would take her. And heartbroken she made her way to the strand, |

|

and sought for the body of Sigmund. And soon she found him. Many and grievous were his wounds, but he still lived. And glad were his eyes as she bent over him and laid her wan face to his. And he spoke and said: “Sorrowful is thy heart, O Hiordis, and young thou art to bear such grief alone.” But she stopped him, crying: “Thou livest, thou livest, and thou shalt live: thou shalt be healed.” But he answered her gently. “Nay: to-day mine eyes have looked upon Odin and my heart bath heard his bidding. I live but to tell thee of the days that are to be, and to comfort thee a little. Lo, yonder where I faced the foemen lies the best of all good swords in pieces. Take them and keep them secure. Odin’s was the gift and to-day bath Odin shattered his gift. Yet do I know full well that a greater than 1 shall bear it. Guard it for thy son and mine. Mine eyes shall not see him, but I joy in his days that shall be. Cherish him, and for him shall this sword be smithied again, and great shall his deeds be on the earth. And sorrow not, O my wife, for sweet and good has been our short life together. And fain am I to rest: full of strife and battle din and longing have been my days, but now is the journey done, and I stand in the lighted doorway, and the king cometh to welcome me; arrayed is the banquet for the feast, and prepared is the bed for rest and quiet dreams.” And the voice of Sigmund faded away, and no more word did he speak. But yet he lived, and Hiordis sat and sorrowed by him till the darkness of night covered them. And when the day broke and the sun |

|

rose, Sigmund turned his head and the first soft beams of sunlight bathed his eyes. And Hiordis bent over him, and lo, he was dead. And Hiordis sat on till the sun rose high in the heavens. And on a sudden she heard a noise out at sea, and she looked up and beheld a great war-ship and many men upon her arrayed for war. And they prepared to beach the ship. And Hiordis rose and flew into the thicket. And the lord of that ship was King Elf, the son of another mighty king who was called the Helper of Men. And King Elf sought water for his shipmen upon the island. And as they drew nigh the shore, they saw that there had been fought a mighty battle. And they beheld the piles of the dead, and among them a living woman, a queen in purple and gold with a crown upon her head. And as they neared the strand she turned and saw them and fled away. And King Elf and his men came ashore, and they looked upon Sigmund, and his face was as the face of a god. And they deemed that here had fallen a great man. Then said King Elf: “Fare we unto the thicket, and there belike we shall find the woman who fled, and she shall tell us the story of these deeds.” So they went into the thicket and found Hiordis, and they spake kindly unto her, and bade her tell them who she was and what had befallen. And when King Elf heard that the mighty man who lay upon the battle-field was Sigmund the Volsung he was amazed, and heavy tidings he deemed it. And Hiordis went with the King and his men |

|

again to the strand. And they set their hands to labour and raised a great mound for Sigmund, and placed him within it. And his right hand was clenched, but it held no sword, and nowhere could they find his helmet or his shield, but they hung the walls of the mound with the cloven shields of the foemen and the banners they had borne. And Hiordis spake to the shipmen concerning the sword of Sigmund and his commands. And they gathered the pieces, and Hiordis took them, and she went aboard the ship of King Elf, and he carried her to his land. And there she abode in the house of King Elf and his father, the Helper. And it befell that the heart of King Elf yearned to Hiordis, and he would fain make her his Queen. And he spake unto her and told her of his desire. And Hiordis answered him: “Thankful am I for thy goodness and thy love, and nought will I gainsay thee, when the time shall serve. But I pray thee, wait till the son of King Sigmund shall be born.” And King Elf rejoiced at her answer, and fain he was to do all as she bade him. And the summer passed, and the winter, and the spring drew on, and Hiordis lived in peace, thinking of the happy past, and dreaming of the happy future. And peace and joy reigned ever in this land of the two kings, and men lived merrily, toiling willingly, and resting quietly when the toil was done. None were over rich, and every hireling had enough, and it was said that a child might go unguarded through the length and breadth of the land, though gold were in his purse and rings of gold |

|

upon his hands. A goodly kingdom it was, well hidden by great mountains, and safe-guarded by a perilous ocean which few men dared to sail. Here abode Hiordis till on a morn of spring the son of Sigmund was born to her. And a great dread fell on all around in that hour, as though some fateful thing had come upon the world. And the serving women looked upon the child and shrank back from the glance of his eyes, so bright and dreadful were they. And Hiordis took him in her arms, and held him to her heart, and spake to him as to one that had understanding. And she told him of the mighty King Volsung, and of Sigmund, his father, and of his last battle and of his death on the island shore. Then she gave him into the hands of the women, and bade them bear him to the Kings, the Helper of Men, and Elf, his son, that they, too, might rejoice with her. And the Helper of Men sat with King Elf and his earls in the great hall, and on a sudden it seemed that they heard sweet voices and the sound of harps, and a great joy came upon them, though they knew not why. Then there entered to them the serving women of Hiordis, and one, who held to her breast a precious burden, stepped to the high seat and unfolded the purple wrappings and gave the babe into the hands of King Elf. And the woman spake and said: “Queen Hiordis sends thee this gift, and she saith the world shall call her son and Sigmund’s by the name that thou shalt give it.” And a great shout of joy from the earls shook the ancient hall, whiles King Elf looked long into the |

|

face of the child. And he deemed that he looked upon a god, so gleaming were his eyes and so bright his face. And at last Elf raised his head and cried: “O Sigmund, King of Battle, the darkness has passed, and lo, here is the dawn: tell us, O mighty Sigmund, how shall we name thy son?” And then uprose an ancient man and he cried “Hail, Dawn of the Day!” and he sang of the mighty deeds which should be wrought by this son of Sigmund. “O, thy deeds that all men shall wonder at, and all gods shall rejoice in! O Sigurd, son of the Volsung!” he cried. And men caught the name and echoed it, and it was heard without the hall, and cried again and again at feast and fair, in street and market, through meadow and forest, over mountain and sea. And Hiordis heard it as she lay in her golden chamber, and her heart rejoiced. And her women came back to her, and gave her the babe, and she cherished him at her breast. And all the glorious Volsung past blossomed again in the minds of men, and they told and sang of the marvellous deeds of old as they sat at the feast, and ever they looked to the coming years for still mightier deeds and still greater wonders. And when the summer came Queen Hiordis was wedded to King Elf, and fair were their days together. Peace and plenty was ever in the land, and the child Sigurd grew up amidst it, waxing in beauty and in strength, and all men blessed him. And as the years sped on, keen and eager of wit and full of understanding did he grow, and oft he sat among the wise |

|

men and listened to their talk of weighty matters. Yet joyous was he withal, and kindly unto every man. Now, there was a man named Regin who dwelt in the house of the Helper. Exceeding old he was, so that none could remember when he came there to dwell. King Elf he had fostered and his father, the Helper, and the Helper’s father before him. Learned in all wisdom was he, and deft in all cunning save the deeds of the sword. Sweet of speech was he, too, so that every word he spake took its right meaning, and skilled he was with the harp strings, and drew from them delight and sorrow; and a great teller of tales was he, and the Master of Masters in the smithying craft, and well he knew the lore of the wind and the weather, and the sea. And on a day Regin came before the Kings, and he said: “O helper of men, I fostered thy youth, and thine, King Elf. Now would I foster Sigurd, for my heart tells me that he shall be a mighty man in the days to come, and no greater master is there than I.” And the Helper answered: “Do thy will herein, O Regin, for thou art the Master of Masters.” So Sigurd abode with Regin, and Regin taught him all things save the craft of battle: the smithying of the sword, and the war coat, the carving of runes, the tongues of many countries, soft speech and song and the music of the harp. And wondrous strong grew Sigurd in body, and he chased the deer of the forest, and the wolf of the wood, and the sea had no terror for him. And on a day he sat with Regin in the smithy, and Regin worked at the gold and told tales of the |

Volsungs and the days gone by. And the boy’s heart swelled, and his eyes brightened as he listened. Then said Regin: “Thou, too, must ride through the world as the kin of early days. Ask now a battle steed of the Helper of Men and King Elf; crave of them that thou mayst choose from among the horses of Gripir.” Now, Gripir was the son of the Helper’s father, but his mother was of giant kin. Far from the seastrand, among the great mountains, he dwelt. A man of few words he was, but all the deeds that had been did he know, and times there were when he saw the deeds that were to come. No sword had he borne since his father fell, and no vengeance had he sought on the slayers. Yet fearless he was, but he desired nought but to learn of the past and to watch the coming days. And Sigurd did as Regin bade him, and he left the smithy and ran to the Kings and said: “Will ye do so much for my asking as to give me a token for Gripir and bid him let me choose a horse from those that run in his meadow?” |

|

And King Elf smiled upon him, and told him he should have his will in the matter, and he gave him a token to carry to Gripir. And well pleased was Sigurd. And in the morning, as soon as the dawn broke, he wended his way unto Gripir. On a crag of a mountain was his dwelling built, and the wild birds flew around it, and the mountain winds swept through every chamber. And Sigurd entered the hall, and there in the midst sat Gripir upon a great chair of ivory. His white beard fell over his golden gown almost to the floor, that was green as the ocean: in his hand he held a kingly staff knobbed with white crystal. And Gripir cried: “Hail, King with the bright eyes! Nought needest thou to show thy token nor to tell thy message. Go choose a horse in my meadow, and he shall bear thee to mighty deeds.” And Sigurd went to the meadow, and lo, by the way he met a grey-clad man, one-eyed and old, and the man said: “Tarry, Sigurd; wilt thou follow my counsel, and get thee the best of all steeds?” And Sigurd answered: “I am ready, what is the deed to be done?” And the man said: “We shall drive the horses to the water and then do thou note what shall happen next?” And they drave all the horses till they came to a great rushing river, and the horses plunged in, but the flood was too strong for them. And some were swept downward and some struggled back to the bank, and some sank: only one of them all swam over to the other side. And he scrambled up the bank, and |

they saw his mane of grey as he galloped in the meadow. Then he wheeled and took to the water again. And the man said: “Once, O Sigurd, did I give thy father, Sigmund, a precious gift, which thou shalt hold dear when the time shall serve. But now do I give thee this horse.” And Sigurd would fain ask him many questions, but the man turned and strode away to the mountains and soon was he lost to sight. And Sigurd hastened to the river bank, and took the grey horse as he came to the shore. And Sigurd thought him the best of all horses, and he leapt upon his back, and named him Greyfell; and the horse seemed to know him, and went gladly beneath him. And men said that this horse was of the blood of Sleipnir, the tireless horse of Odin. And a joyous song poured from Sigurd as he wended his way to the Helper and King Elf borne on the back of Greyfell. And the days passed, and Sigurd waxed ever fairer and stronger, and well-loved was he by all, and happy were his days. Yet oftentimes, he looked towards the |

|

mighty mountains with a great wonder in his heart as to what lay beyond them, and a great longing sprang up in him for the wide world and its knowledge and its deeds. And he said to himself: “This land is not the land of my blood, and my mother bath other sons, and they shall be kings, and I must needs serve them. Fain would I go forth and do great deeds, yet must I wait till Odin calleth me.” And it befell on a day that he sat in Regin’s hall, and Regin told him many stories of old kings who had fared forth and sought their kingdoms. And Sigurd’s heart was heavy as he listened. And at last when he had made an end of his story Regin cried: “Thou art the son of King Sigmund! Why dolt thou waste thy years in this little land, where others will be kings and thou must serve them.” And Sigurd answered him: “Well do I love this sweet and peaceful land, yet full fain is my heart for the land of my fathers. But, meseemeth, when the deed is ready, Odin shall call me to it, and in nowise shall I lack.” Then said Regin: “The deed is ready even now, yet to hold my peace is best, for thou lovest this land and thy life of quiet days too well to fare forth into strife and danger. Yet do they say that Sigmund was thy father: but fear nought from him; he lieth quiet in his mound by the sea.” Then shone the eyes of Sigurd like a flame at Regin’s words of scorn, and his voice rang out like the thunderpeal. “Tell me,” he cried, “thou Master of Masters. |

|

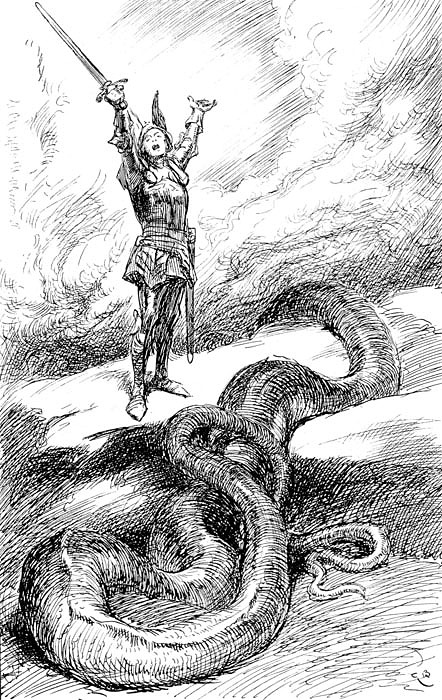

what is the deed that is ready? Mock me no longer or the day of my birth thou shalt rue.” Then answered Regin: “The deed is the righting of wrong, and the winning of untold treasure that should make thee more than a king. Long is it since I first came here to seek a man for my need, for the treasure is mine, but nought can I do to end the days of my waiting and my woe, for my hand is frail, and my heart herein avails not. Yet have I long known that in this land should I find the man for the deed, and I knew that my waiting was done when I looked on thine eyes in the cradle.” Then said Sigurd: “I will do the deed, and thou shalt have the treasure, but on thy head he the curse, if curse there be with the gold. But full strong in my heart to-day are the dreams of my youth, and I long to look on the world and meet with mighty men, and try my skill at their feats. So tell me, O Master of Masters, the tale of this treasure of thine, and the deed to be done.” And the look of scorn went from the face of Regin, and now was he full content. “Sit,” he said, “thou son of Sigmund, for hereof must a tale be told: sit, and hearken of wondrous matters, of things unheard, and deeds of my beholding.” And Sigurd sat him down upon the heaped-up unwrought gold, and Regin began his story. “Know first,” he said, “that I was born of the race of the dwarfs. Mighty we were in the days that I speak of, but now our days are done. Before the gods came upon the earth, and before the days of |

|

men, did we live, and fair was the earth, and exceeding glad was our life. Bear with me, O Sigurd, for while I speak of the days that are past, I scarcely can think they are wholly o’er. Then came the gods to earth, and hopes and fears arose within us, and unrest, and toil. We fell to the working of metals, and we fashioned spear and bow, and sought out the secrets of the deeps of the earth, and dealt in venom and leechcraft. “Reidmar the Ancient was my father, a king he was, old and covetous. His youngest born was I, and to me and my brothers’ twain did he give such gifts as would work his will. To Fafnir, the eldest born, he gave the fearless soul, the pitiless heart, and the greedy hand. To Otter, his second son, he gave the cunning for the snare and the net, and restless longing and mighty strength; and to me, grief and fear, the skill of the smithying craft, toil, and the longing unsatisfied heart. “Worse were we now than the gods, for of all our ancient might but one thing had we left: the power to change our bodies into bodies of the beasts, or the fishes, or the fowls. “So did we live together. I toiled and toiled, building my father a hall. And fair it was, but my toil had made me grim and cold-hearted, and my hands were twisted and foul, and nought did I know of the glorious world, of the sun, and the wind and the flowers, nor had I the skill of the sword and the shield. “But Fafnir, my brother, fared forth, leaving no wrong undone, and Otter would change his shape with the beasts and the fowls and the fish, and he knew |

|

their joy and their grief, and all knowledge of them he had, that he seemed the king of the creatures. “Now, it befell on a day that three gods came to the earth in the shape of men: Odin the All-Father, and Loki the Evil-hearted, and Hœnir the Blameless. And they came to a mighty water, and upon the shore lay my brother Otter, his body changed to an otter indeed. And Odin and Hœnir passed on, but Loki saw through the shape of the otter and beheld the mighty dwarf. And, ever evil of heart, he tore a piece from the rock and hurled it, and smote my brother, Otter, that his man’s life passed away. And wroth was Odin at this deed of Loki, but he said nought, and the three fared on again together till they came to a grassy plain. And there they saw a noble house and a hall full glorious and fashioned with great craft. And night was falling, so they sought shelter there. And they went up to the porch, all smooth wrought with gold, and into the hall, so wondrous fair with its windows and pillars and golden hangings that even the gods marvelled at its beauty. “And in the hall sat a king upon a throne, clad in purple robes, with a crown upon his head. And seeming kindly were his words as he bade them rest and join the feast and be merry. And they sat at the board and joined in the laughter, yet did they feel themselves caught as in a net, and no escape could they think of from their man-like bodies. “And anon the old king’s laughter lost its mirth and seemed full of mockery. And at last he spake and said: ‘Well I know ye to be gods, but guilty are |

|

ye of a great wrong, and to no feeble folk shall ye make answer. Time was when we knew you not, and needed you not, and fair were our days, but now do we toil and strive and suffer, and our might is gone from us. Well do ye wot that I am Reidmar, and that ye have slaughtered my offspring, and to-day will I undo the work of your hands, and run the web of the world backward unless ye give one my heart’s desire!’ “And Odin answered him: ‘Wrong indeed have we done thee, and if thou wilt amend it with wrong, nought can we gainsay thee. For thine heart’s desire is gold, and gold thou shalt have, yet best it were that thou lackest it.’ “Then cried Reidmar, and Fafnir, his eldest son, and I, Regin the Smith: ‘Pay us the ransom of blood or ye shall die and we will be gods!’ “Then said Odin, and his voice was awful: ‘Give doom, O Reidmar! What is the gold thou wilt have?’ “And Reidmar answered: ‘Give me the gold that Andvari hideth at the bottom of the sea.’ “And Odin bade that Loki should be loosed, and I loosed him, and he went at Odin’s word to seek the golden hoard. And over the mountains he went to a mighty water, and there dwelt Andvari, and an Elf of the Dark is he. Once was he wise and great, but now did he heed nought but the gathering of gold. And the all-guileful Loki set his snare and entrapped the Elf, and forced him to give up the treasure. There was the Helmet of Dread, and the Hauberk of Gold, and great heaps of precious things. And Loki commanded Andvari to bring them all up to the earth, and this the |

|

Elf did, while Loki laughed aloud at his groans and grief and weariness. “And when all was done, and Andvari hurriedly turned to go back, Loki saw upon his hand the gleam of gold in the sun. And he cried: ‘Come hither again and deliver the ring from thy finger.’ And the Elf gave up the ring, and his anguish was great as he parted from it. And he cried in his wrath: ‘Could I give thee worse than what thou bearest, right fain am I to give it, but a curse thou bearest, and the woe that is now mine shall come to many another with my gold. Brethren and fathers and kings shall it slay, and the hearts of fair queens shall it break, and the light of day shall be as darkness!’ “But Loki laughed at his woe, and gathered up the treasure, and carried it with all haste to the hall of Reidmar. And when we saw it gleaming there, we stood before it panting, so great and rich and glorious was the sight. “And Odin spake, and his voice was cold and dread: ‘O Kings, behold the ransom, duly paid,’ he said. “And for a space Reidmar answered nought, but ever his eyes peered up and down and athwart the pile as though he searched for something more. Then he caught the flash of the golden ring on Loki’s hand, and wroth, he cried: ‘O Loki, master of guile, cast down Andvari’s ring.’ And Loki drew off the Elf-ring and cast it upon the pile, saying: ‘Right joyful am I that all of the gold thou shouldst take, that none of the curse thou mayst lack.’ |

|

“And I loosed the gods, and mighty they stood for a moment, then turned and went out into the night. “And there the treasure lay, and its golden gleam fell upon Reidmar and Fafnir and me. And my heart was full of greed and longing to hold it as my own. Yet did I smile, and bid my father keep the more part for himself, but give unto Fafnir and me a little as recompense for such deeds of help as we had wrought. “But Reidmar answered me nothing, but sat on his ivory throne, gazing with glistening eyes upon the flaming pile. And Fafnir spake never a word, but glared upon our father with fiery, wrathful eyes. “And the night fell and the morning dawned, and still sat Reidmar there in his purple robes gazing upon the gold. And Fafnir took his sword, and I took my smithying hammer, and we went our ways in the world. And when the evening was come, I went back to the hall. But weary and spent was my heart, and so great was still my longing for the gold, that I durst not look upon it again. So I lay in the smithy and slept, and methought now and then that 1 heard the tinkling of metal, and that I saw a light in the hall. But I held all as dreams, till a dreadful cry rang out in the darkness, and there was a sudden clashing of swords. “And I leapt from my bed and ran to the hall, and there by the pile of the gold stood Fafnir, my brother, and there at his feet lay Reidmar, and his blood flowed amid the glittering hoard. And I rushed to my father’s side, but even as I bent and looked into his eyes they darkened in death. Then I turned me and looked upon Fafnir, and I trembled as I saw |

|

upon his head the Helmet of Dread, and on his body the golden Hauberk, and in his hand was his sword, and both hand and sword were red with our father’s blood. Nought could I speak, but at last he cried with a dreadful voice: ‘Dead is Reidmar at my hand, that alone I may hold the treasure. Alone will I dwell henceforth and be a mighty king, and the gold shall grow in my keeping. Be thou gone, or thy blood will I add to my guilt.’ “And cold and terror-stricken I fled from the hall which my hands had fashioned so gloriously, with nought in the world of my own but my longing heart and my craft-skilled hands. “And I came unto this land, and I taught its people many things. And for many generations have I wrought among them. And once I journeyed back to the land of my birth, and I found the golden house which my hands had builded, ruined and open to the sky, and I looked within the great hall, and piles upon piles of gold I saw, and lo, a mighty serpent crawled to and fro amongst it. And I remembered our ancient power of changing our bodies at will, and I knew that the serpent was Fafnir. “And again I fled and returned to this land, and greater and greater grew my longing for the gold, and lesser and lesser my hope. But then, O Sigurd, was thy father’s father born, the mighty Volsung, and I began to dream dreams. And the years passed on and thy mother came to this land, and thou wert born. And I looked upon thy eyes, and my heart told me that thou wert he who should bring me rest. And |

|

the gold shall he mine, and the craft, and the gathered wisdom of Fafnir, and great deeds will I do, that shall win the love of all people, and my name that once was as naught shall be remembered and sang, and death shall be no more, and the world shall be ever fair!” And Regin’s words faded away, and his eyes closed, and seemed to fall into slumber. And the flames leapt up in the smithy and shone upon the Master, and Sigurd sprang to his feet and drew his sword, and cried: “Awake, O Regin, for the days go by Awake, for the deed is yet to do.” And Regin wakened with a groan, and sad and worn and old was his visage. And he seemed as a man bowed down by a burden. And he looked upon Sigurd and spake, and his words came thick and fast “Hast thou hearkened, Sigurd?” he said. “And wilt thou help a man that is old and weak to avenge his father? Wilt thou win back the Treasure of Gold? Wilt thou rid the earth of a wrong, and my heart of its sorrow and woe?” And he drooped and trembled before Sigurd, fearful for his answer. And Sigurd said: “Thou shalt have thy desire and the treasure, O Regin, but take thou also the curse on thy head.” And they parted. And on a day Sigurd came again to Regin in the smithy, and said: “A gift at thy hands I ask: Forge me a sword for the deed.” And the Master answered: “Lo, here is a sword wrought for thee with many a spell and charm and all the craft of the Dwarf-kind. Be glad and sure in |

|

it and well shall it stead thee in the task.” And Sigurd said never a word, but he looked on the sword, and saw its gemmed and golden hilt, and its blue, bleak blade. And with flaming eyes he sprang to the anvil, and smote it with the sword. And lo, the sword fell shivering in pieces to the earth. And wroth was Sigurd, and he cast the jewelled hilt amongst the ashes, and strode from the smithy, and for many a day he came not back. And Regin toiled, night and day fashioning another sword, and at last when two moons had come and gone, Sigurd stood before him once more. And he said to Regin “What hast thou done, O Master, in the forging of the sword?” And Regin answered: “Lo, a blade have I forged which shall surely please thee. Night and day have I toiled at it, and the cunning has left my hand, if this be not to thy mind.” And Sigurd took the sword, and Regin shrank from the flaming brightness of his eyes. And again Sigurd stood before the anvil, and he smote it, and again the sword lay broken upon the floor of the smithy. And no word did he say, but he cast the hilt from him, and strode off to the hall of the kings, and merry he was that night at the feast. And when the morn was come, he went to his mother and said: “Give me the sword, my mother, that Sigmund gave thee for me, and let me fare forth in the world.” And Hiordis looked into his face and saw the fire in his eyes, and she said: “Gladly will I give it thee.” |

|

And she took his hand and led him to her treasure-chamber. And she unlocked a golden chest, and opened it, and lifted the purple coverings that lay within. And there were the pieces of the sword of Sigmund. No spot of rust stained them, and the gems in the hilt were as bright and glorious as when they had first flashed in the Volsung hall. And Sigurd rejoiced, and he bent and kissed Hiordis as he took the pieces from her hands. But never a word she spake, but stood and gazed upon him. So glorious and fair was his face, and young as are the immortal gods. And long she stood there after he had left her, like one awakening from sad dreams to glorious life. And Sigurd went swiftly to the house of Regin. And there in the doorway of the smithy stood the Master. And Sigurd put the pieces of the sword into his hands, and Regin looked upon them long. And his face was dark and grim as he spake. “Will nought serve thee but this blade of thy father’s?” he asked. And Sigurd answered: “Get thee to thy craft. Nought will I have but this sword, and if thine hand fail me in this, then will mine own hand fashion it, for here is the slayer of the serpent.” And Regin said: “Thou speakest truth. This sword shall slay the serpent, and do many another deed. But now get thee gone, and come to me again when the May month is upon us, and thy sword shall be ready for thee.” And Sigurd went his way to the dwelling of the kings, and quiet and joyous passed his days till the |

|